October is Energy Awareness Month

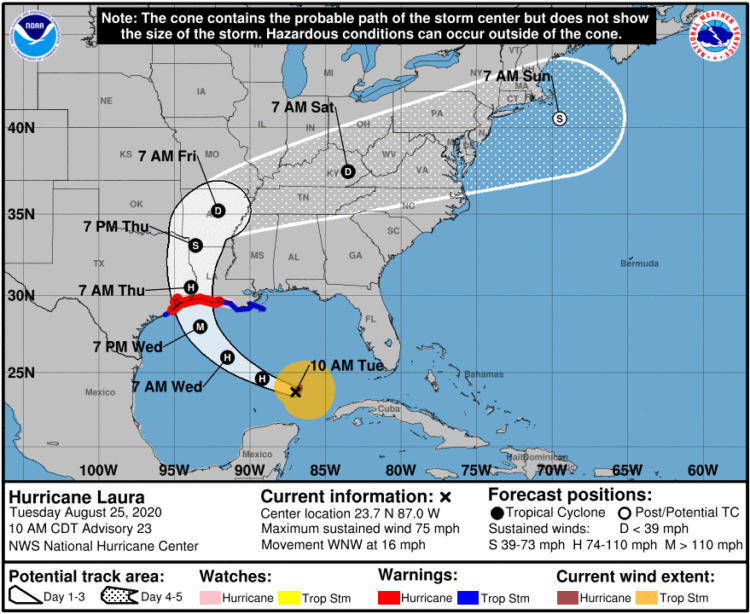

Power outages (i.e., when the electrical power goes out unexpectedly) and precautionary power shutoffs are happening more often because of and to prevent emergencies. These emergencies include disasters, such as hurricanes and wildfires.

The U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) says, on average, U.S. electricity customers experienced just over 8 hours of electric power interruptions in 2020. That was the most since EIA began collecting electricity reliability data in 2013.(1)

The EIA further reported that customers in Alabama, Iowa, Connecticut, Oklahoma, and Louisiana experienced the most time with interrupted power in 2020. Severe weather was a factor in all these states.

- Alabama experienced several hurricanes, including a direct hit from Hurricane Sally.

- Tropical Storm Isaias left about 750,000 electricity customers in Connecticut without power. Some didn’t have power for over a week.

- A derecho affected Iowa and other parts of the Midwest. It caused widespread power outages, damaged grid infrastructure, and forced the early retirement of Iowa’s only nuclear power plant.

- An ice storm in October was to blame for widespread power outages across Oklahoma.

- Louisiana experienced three hurricanes and two tropical storms.(1)

The impacts of power outages and power shutoffs are felt by everyone. Here are some ways you can prepare your health for a power outage.

Be Power Prepared

Be prepared to be without electricity during an emergency and, possibly, for several days after.

A power outage can affect people’s ability to use devices and the availability of refrigeration. This makes it especially important that people who rely on durable medical equipment and refrigerated medicines like insulin take steps to prepare. For example:

- Identify emergency lighting, safe heating alternatives, and backup power sources for your mobile devices, appliances, and medical equipment.

- Create an emergency power plan that includes model and serial numbers for your medical devices.

- Read the user manual or contact the manufacturer to find out if your medical device is compatible with batteries or a generator.

- Fully charge your cellphone, battery-powered medical devices, and backup power sources if you know a disaster, such as a hurricane, is coming.

- If possible, buy manual alternatives for your electric devices that are portable, dependable, and durable. For example, a manual wheelchair, walker, or cane as a backup for an electric scooter.

Power outages can also put people at increased risk for post-disaster hazards, such as food and carbon monoxide poisoning.

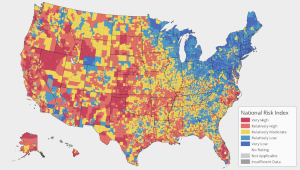

The effects of emergencies, such as power outages, are experienced differently by different populations.

The places of our lives, including our neighborhoods and built environment, can influence our experience with emergencies.(2)

People who live in rural areas and places with an aging infrastructure may experience more frequent and longer-lasting power outages and face greater adversity because of it. They may also have limited access to the supplies they need to prepare for power outages.

Planning for Power Outages

People who use electricity- and battery-dependent assistive technology and medical devices must have an emergency power plan in case of a power outage.

Checklists are a way to break large jobs down into smaller chores. They can help you pack for a trip, grocery shop, and even prepare for emergencies.

The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) National Network’s emergency power planning checklist is for people who use electricity and battery-dependent assistive technology and medical devices. These include:

- Breathing machines (e.g., respirators and ventilators).

- Power wheelchairs and scooters.

- Oxygen, suction, or home dialysis equipment.

The Food and Drug Administration’s “How to Prepare for and Handle Power Outages” guide for home medical device users is another useful planning resource. Use it to organize your medical device information, identify the supplies for the operation of your device, and know where to go or what to do during a power outage.

Health Care Preparedness

A power outage or shutoff can limit the operations of hospitals, outpatient clinics, pharmacies, and other patient-care facilities.

Healthcare facilities need electricity to care for patients, provide services, and “keep the lights on.” Since many facilities have resident populations, hygiene and feeding are also part of the electrical demand.

Resilience to power outages begins with the leadership at the facility. Here are some resources to help healthcare facilities plan for and respond to public health emergencies.

- Planning for Power Outages: A Guide for Hospitals and Healthcare Facilities

- Healthcare Facilities and Power Outages: Guidance for State, Local, Tribal, Territorial, and Private Sector Partners

- Protecting Patients When Disaster Strikes: A Playbook for Safeguarding Emergency Power Systems for Rhode Island’s Critical Healthcare Facilities During Extended Power Outages

Additional resources to help healthcare systems and hospitals plan for public health emergencies are available on the CDC website.

Resources

References

- https://www.eia.gov/todayinenergy/detail.php?id=50316

- https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/placeandhealth/howdoesPlaceaffectHealth.html

Thanks in advance for your questions and comments on this Public Health Matters post. Please note that CDC does not give personal medical advice. If you are concerned you have a disease or condition, talk to your doctor.

Have a question for CDC? CDC-INFO (http://www.cdc.gov/cdc-info/index.html) offers live agents by phone and email to help you find the latest, reliable, and science-based health information on more than 750 health topics.

Managing Asthma During COVID-19

Managing Asthma During COVID-19 Headed Out? How to Stay Healthy When Running Essential Errands

Headed Out? How to Stay Healthy When Running Essential Errands Prepare Your Health for the 2020 Hurricane Season

Prepare Your Health for the 2020 Hurricane Season AFM is Serious: Know the Symptoms. Act Fast.

AFM is Serious: Know the Symptoms. Act Fast.