Two papers that I co-authored with colleagues at Lancaster and Massey Universities appear this month in the October 2010 issue of Epidemiology & Infection. The common theme is that cryptic differences in the population structure of the enteric pathogen Campylobacter jejuni, revealed by my method for attributing cases to source populations, suggest subtle differences in transmission between rural and urban districts.

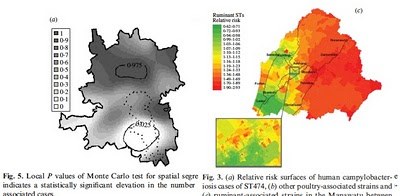

The method, implemented in the software iSource (available on my website), allows strains of campylobacter to be characterized as poultry- or cattle-associated based on their genetic profiles. Interestingly, when the relative incidence of poultry- and cattle-associated strains is plotted on a map, there is a significantly higher occurrence of poultry-related disease in urban areas and cattle-related disease in rural areas. Both studies – one in Lancashire led by Edith Gabriel and one in New Zealand led by Petra Mullner – draw the same conclusion. These findings imply that there are subtle differences in transmission in rural and urban areas. Whether they represent geographical differences in the profile of food pathogens, environmental exposure, resistance to infection or other risk factors is not understood.

Category Archives: Petra Mullner

Posted by in Campylobacter jejuni, Edith Gabriel, Epidemiology, Petra Mullner

Campylobacter source attribution in New Zealand

What is the source of the common food poisoning pathogen Campylobacter jejuni was the subject of a paper published in September last year in PLoS Genetics by my colleagues and I, in which we traced the origin of bacterial isolates collected from patients in Lancashire, England. In that study, and a subsequent investigation into campylobacteriosis across Scotland, we found that the majority of cases could be attributed to populations of C. jejuni typically found in poultry.

What is the source of the common food poisoning pathogen Campylobacter jejuni was the subject of a paper published in September last year in PLoS Genetics by my colleagues and I, in which we traced the origin of bacterial isolates collected from patients in Lancashire, England. In that study, and a subsequent investigation into campylobacteriosis across Scotland, we found that the majority of cases could be attributed to populations of C. jejuni typically found in poultry.Now Petra Mullner, Nigel French and colleagues have genetically characterized the C. jejuni populations found in human patients, cattle, sheep, poultry and environmental samples from New Zealand covering the period March 2005 - February 2008. What is special about their study is that the New Zealand poultry industry is a closed system, with no foreign imports, making it possible to directly sample the putative source populations and disease-causing isolates concurrently.

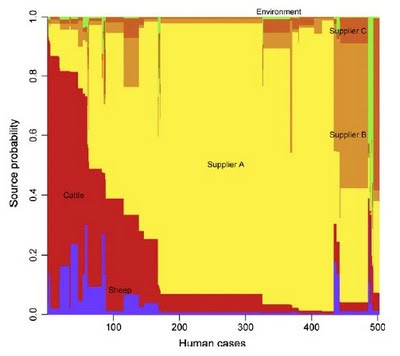

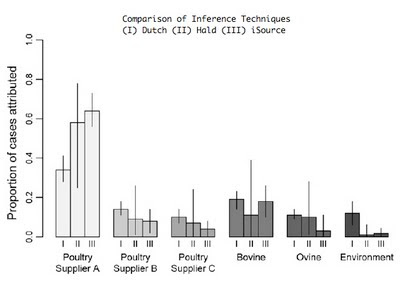

Like the studies in England and Scotland, poultry was the inferred source of the majority of disease in New Zealand. Uniquely however, it was possible to attribute cases separately to the three major poultry suppliers on the islands. One supplier in particular was attributed a disproportionate number of cases using 3 assignment methods, including my method (iSource, soon to be available on this website). Supported in part by this evidence, the New Zealand Food Safety Authority introduced mandatory targets for limiting Campylobacter contamination of poultry products in 2007. Remarkably, the number of cases fell from 15,873 in 2006 before the control measures were introduced to 6,689 in 2008. The next chapter of this intriguing story will be a follow-up study to establish whether the fall in the number of cases corresponded to a reduction in the proportion of campylobacteriosis attributable to poultry sources.

Posted by in Bacteria, Campylobacter jejuni, Microbiology, Nigel French, Petra Mullner