This student-authored post is published by CPR in partnership with Medill News Service and the Northwestern University Medill School of Journalism, Media, Integrated Marketing Communications. The views and opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect the views, policies, or positions of CPR or CDC.

During an emergency, the right message, from the right person, at the right time can save lives. That’s assuming people can find, understand, and use the information.

Many people who are Deaf and hard-of-hearing rely on sign language interpretation and captions to receive information. The inability to provide real-time interpretation and captions during an emergency can endanger lives.

In Arizona, where nearly 17% of people have a hearing loss, the Arizona Department of Emergency and Military Affairs (DEMA) has created an American Sign Language (ASL) glossary of emergency management terms to improve access to information during emergencies.

The ASL glossary website features a series of videos. The videos are a training resource for Emergency Response Interpreter Credentialing (ERIC) program interpreters and a reference for Deaf community members who are unfamiliar with emergency management terms.

Victoria Bond, Community Outreach Coordinator for DEMA, leads the team that created the glossary. The team included Certified Deaf Interpreters (CDI) Beca Bailey and Shelley Herbold.

CDIs are members of the Deaf community who know and understand Deaf culture. Their linguistic expertise helped account for nuances in ASL, which evolve like any other spoken language, Bailey said.

“The language [ASL] is complex,” said Bond, an experienced interpreter in her own right. “The glossary was created to standardize language around emergencies for interpreters and the Deaf community.”

But emergency management is also complex. Interpreters needed to learn about the Incident Command System and the terminology before they could create accurate interpretations. They took online training and spoke to response experts to broaden their understanding and create a list of possible terms for the glossary.

The team drafted signs for the terms. They shared the signs with other trained interpreters and Deaf professionals in emergency response to ensure that they were clear and accurate. Their feedback was used to decide which signs to include in the glossary.

So far, the team has created and recorded over 150 terms for the glossary. Related terms are grouped into the same video.

The glossary was made possible with funding from the Arizona Department of Health Services and is an outgrowth of DEMA’s ERIC. Bond is the program director.

The ERIC program trains American Sign Language (ASL) interpreters and Communication Access Realtime Translation (CART) captioners on the Incident Command System, integrating into an emergency response team, content, and vocabulary for all-hazard incidents. ERIC trained personnel deploy statewide to support state and local emergency response agencies.

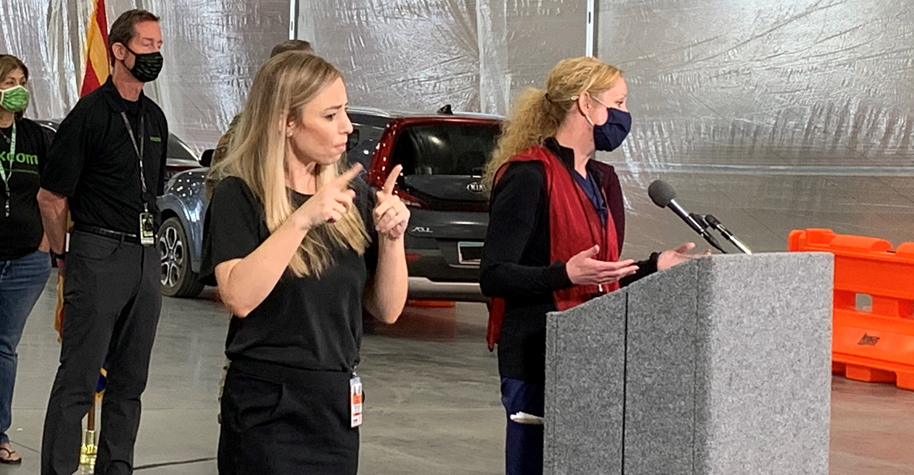

Interpreters and captioners attend media briefings, town hall meetings, and livestreamed meetings. They interpret and transcribe emergency information in real-time for people who are Deaf and hard of hearing.

The alternative is to add sign language interpretations and captions to recordings after the event. Bond says that’s too long to wait for emergency information, especially in life-threatening situations.

Bond recalls a deployment to Coconino County, Arizona, in July 2019. She provided interpretation services during a town hall meeting. One community was under an evacuation order. Fifteen others were under an evacuation watch. In situations like that, making time-sensitive information accessible cannot be an afterthought.

“The goal of ERIC is to provide real-time access to emergency information,” said Bond. “If information is being livestreamed or broadcast on television, we want it immediately accessible and understandable to people who are Deaf and hard-of-hearing.”

“The glossary helps advance that goal,” she continued. “If someone watching doesn’t recognize a sign, the glossary is there for their use and understanding.”

Bond thinks of the glossary as a living resource that DEMA will continually edit and update.

“We plan to continue to add terms,” said Bond. “As the community and our team of interpreters use the glossary and become familiar with it, we’ll use their feedback to determine what terms are missing. We may also add longer videos that give more detailed information about a specific topic.”

Visit the Arizona Emergency Information Network website to access the ASL glossary and the DEMA website for more information about the ERIC program.

Resources

- Public Health Matters: Arizona’s ERIC Program Works to Improve Access to Emergency Information

- Disaster American Sign Language (ASL) Videos

- COVID-19 ASL Video Series

Thanks in advance for your questions and comments on this Public Health Matters post. Please note that CDC does not give personal medical advice. If you are concerned you have a disease or condition, talk to your doctor.

Have a question for CDC? CDC-INFO (http://www.cdc.gov/cdc-info/index.html) offers live agents by phone and email to help you find the latest, reliable, and science-based health information on more than 750 health topics.