Category Archives: Australia

Koalas, Chlamydia, Antibiotics and Microbiomes – what else do you need?

Posted by in Antibiotics, Australia, Chlamydia, IndieGoGo, Koalas, microbiomes

H. floresiensis or H. sapiens with Down syndrome? Plus landing on a comet

Lords of the zings

I don’t know why the new papers about the “hobbit,” the 2003 find of tiny ancient bones from the Indonesian island of Flores, have made such a splash. No, I take that back. I do know. …

The post H. floresiensis or H. sapiens with Down syndrome? Plus landing on a comet appeared first on PLOS Blogs Network.

Posted by in Astronomy, Australia, comets, Down syndrome, esa, European Space Agency, Flores, hobbit, Homo floresiensis, Homo sapiens, Human Evolution, LB1, Mars, media criticism, NASA, National Aeronautics and Space Agency, On Science Blogs, paleoanthropology, Research, Rosetta, science blogging, Science Journalism, Siding Spring

Phillip Island

Everything about this post is very small: it’s very short because I only have a few minutes, and it’s about little penguins. That’s what they’re called: Little Penguins.

Little penguins live along the coast of New Zealand and the south of Australia, and are, as advertised, not very big. They’re about the size of a chicken or duck, if not smaller.

I’ve seen them both at Melbourne Zoo and at Phillip Island, an island close to Melbourne. At Phillip Island, you can even watch the penguins on their “penguin parade“, when they return to the island at night. You’re not allowed to photograph them, so it’s hard to find pictures of it online, but someone uploaded an old video to YouTube:

Adorableness starts about a minute in, and then gets increasingly cuter as the penguins get closer.

Filed under: Have Science Will Travel Tagged: Australia, penguin

Posted by in Australia, Have Science Will Travel, penguin

Uluru and Kata Tjuta

I’ve been busy lately, as you may have noticed by my lack of posts. I desperately need a vacation, but since that’s not an option, I can look at some of my favourite photos of previous vacations. Like this photo of sunrise at Uluru:

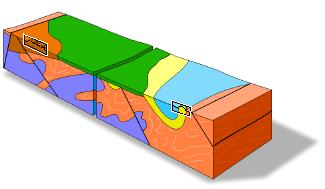

Uluru is the iconic enormous rock that sits all by itself in the middle of the Australian desert. It looks so imposing and out of place that you can’t help but wonder how it got there. Australia’s indigenous people have had explanations for the rock for ages, all involving spiritual stories. Both a government website and the site of the local tourist resort are unable to share those tales, though, because the stories are restricted by sacred rules. Luckily for us, geologists are more forthcoming with their interpretations about the origin of Uluru, as well as the neighbouring rock formation Kata Tjuta.

About 500 million years ago, the area around Uluru and Kata Tjuta wasn’t a desert, but a sea. It’s hard to imagine the sea at all when you’re in the middle of a huge desert, about a day’s journey away from the closest coast.

When the sea receded, the rock layers below started folding, and when the sandier layers eroded over time, the edges and bumps of some of the underlying layers became visible. Uluru is the edge of a rockslab that extends for several kilometers underground. The stripes are the layers that would normally be horizontal (and underground). Kata Tjuta are folds in the rock layer that have been pushed upwards.

When the sea receded, the rock layers below started folding, and when the sandier layers eroded over time, the edges and bumps of some of the underlying layers became visible. Uluru is the edge of a rockslab that extends for several kilometers underground. The stripes are the layers that would normally be horizontal (and underground). Kata Tjuta are folds in the rock layer that have been pushed upwards.

The geological explanations are probably not as entertaining as the origin stories that the local population have about Uluru and Kata Tjuta. When I visited there were a few that were pointed out: large animals crawling over the rock, for example. But as far as scientific explanations go, this one is also pretty amazing, I think!

And don’t forget to check out our Have Science Will Travel map:

Filed under: Have Science Will Travel Tagged: Australia, geology

Posted by in Australia, geology, Have Science Will Travel

A lighthouse keeper warns vessels of Margaret Brock Reef in…

A lighthouse keeper warns vessels of Margaret Brock Reef in Australia, April 1970.

Photograph by Joe Scherschel, National Geographic

Posted by in 1970's, Australia, lighthouse, natgeo, Scherschel, Vintage

A shark guides migrating salmon into the shallows off Baxter…

A shark guides migrating salmon into the shallows off Baxter Cliffs in Australia, April 1995.

Photograph by Sam Abell, National Geographic

Meet the Lord Howe Island Stick Insect

Photo credit: Rod Morris http://www.rodmorris.co.nz

Dryoceocelus australis lives solely on an island group in Australia. They were thought to be extinct after 1930 until two dozen were spotted again in 2001. The IUCN lists them as critically endangered currently.

Read more here about the conservation efforts by zoos in Australia to ensure the species survival.

Pair bonding between the male and females has been reported, but is not definitive. Anecdotal evidence suggests the Lord Howe stick insects are gregarious and thus finding a male and female together may just be the expression of this trait. Research from Patrick Honan in 2008, examined 9 pairs from the Melbourne Zoo found that the behavior was consistent for each pair daily, but varied depending on the pair. Some pairs were always found together, but in some cases the female would be found in the nesting box and the male outside the nesting box.

Finally, here is an amazing video of hatching Lord Howe island stick insects from Zoos Victoria if you haven’t seen it already.

Lord Howe Island Stick Insect hatching from Zoos Victoria on Vimeo.

“Meet the…” is a collaboration between The Finch & Pea and Nature Afield to bring Nature’s amazing creatures into your home.

Posted by in Australia, Curiosities of Nature, Dryococelus australis, Lord Howe Island, meet the, Phasmatodea

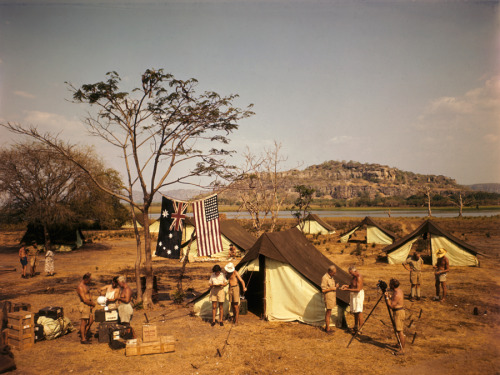

The base camp of an expedition to Arnhem Land,…

The base camp of an expedition to Arnhem Land, Australia.

Photograph by Howell Walker, National Geographic