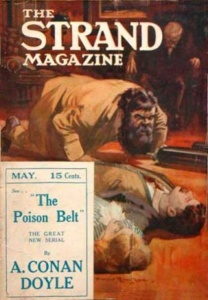

Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Poison Belt (1913)

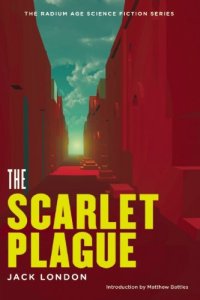

End of the world narratives are typically about a fight for survival – people fight for food, shelter, and safety as the asteroid, pandemic plague, or zombie hordes threaten to wipe out human life. This was just as true of SF a century ago as it is today: In 1912, Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague featured armed Berkeley professors, holed up in the chemistry building as a plague swept away civilization; while Garrett Serviss’ The Second Deluge tells of a thousand lucky survivors who, in a modern ark, escape a world-wide flood.

End of the world narratives are typically about a fight for survival – people fight for food, shelter, and safety as the asteroid, pandemic plague, or zombie hordes threaten to wipe out human life. This was just as true of SF a century ago as it is today: In 1912, Jack London’s The Scarlet Plague featured armed Berkeley professors, holed up in the chemistry building as a plague swept away civilization; while Garrett Serviss’ The Second Deluge tells of a thousand lucky survivors who, in a modern ark, escape a world-wide flood.

The next year, Arthur Conan Doyle also published a novel about a group of hardy survivors. But the terms of survival in The Poison Belt are much more ironic: Professor Challenger and his fellow adventurers, who had fought off dinosaurs and ape-men on a remote South American plateau in Doyle’s 1912 The Lost World, now confront the extinction of human life as passive observers, watching the destruction of humanity from the window of the “charmingly feminine sitting room” of Professor Challenger’s wife.

The Poison Belt does have the scenes of destruction and ruin that we’ve come to expect in this genre. But most of this remarkable novel centers on existential conversations that take place in a single, comfortable room – a setting that anticipates Samuel Beckett’s classic apocalyptic play, Endgame (1957). In this setting, Doyle explores humanity’s role in the universe – a role that, by 1913, was being reevaluated after decades of scientific discoveries revealed that the earth was much older and the universe much larger than had been recognized. As the cosmic stage grew, humanity’s role shrank, raising the possibility that we might not in fact be the central characters we thought we were – and that we might be forced to exit long before any final act.

The Atavistic Super-Scientist

The premise of The Poison Belt is similar to that of Garrett Serviss’ pulp story The Second Deluge, published just the year before. In both books, the earth – whose trajectory through the universe is completely beyond all human control – passes through a cloud of something that threatens all life. (Ted Thomas and Kate Wilhelm would turn to this premise again in 1970, in The Year of the Cloud.) In Serviss’ story, this cloud is a watery nebula. A brilliant, iconoclastic super-scientist correctly recognizes the threat, revealed by some puzzling astronomical data, and builds a high-tech ark that saves 1000 carefully selected people from the inevitable flood.

A super-scientist, Professor Challenger, is the lead character of Doyle’s novel as well. Challenger also recognizes a poisonous cosmic cloud by correctly interpreting mysterious astronomical data, and prepares an ark of sorts, in which he faces the end of the world with a few select friends.

A super-scientist, Professor Challenger, is the lead character of Doyle’s novel as well. Challenger also recognizes a poisonous cosmic cloud by correctly interpreting mysterious astronomical data, and prepares an ark of sorts, in which he faces the end of the world with a few select friends.

But in spite of the parallels with Second Deluge, The Poison Belt‘s ironies make for a much richer, more interesting novel. One irony is the super-scientist himself: unlike the typical scientist hero of pulps SF, Professor Challenger is both genius and atavism; a short, hairy, and quarrelsome man who bellows and grunts like an animal, but behind whose heavy, Neanderthalish brow sits a formidable brain. And Challenger’s ark is not a high-tech engineering marvel; it’s his wife’s boudoir, made air-tight with some varnished paper.

How Challenger and his friends end up in Mrs. Challenger’s sealed room is told as a first-person account by E.D. Malone, a London-based journalist who was with Professor Challenger on his South American adventures in The Lost World. Malone is sent by his editor to interview Challenger, who has just published a baffling warning letter in today’s paper.

In the letter, Challenger argues that there is a link between some recent, unexplained blurriness in the spectrographic data collected by astronomers, and a mysterious, disabling illness that is afflicting Sumatra. Challenger, somewhat cryptically, suggests that the cause of both is is that our solar system is beginning to drift into a possibly toxic zone of the universal ether.

In the letter, Challenger argues that there is a link between some recent, unexplained blurriness in the spectrographic data collected by astronomers, and a mysterious, disabling illness that is afflicting Sumatra. Challenger, somewhat cryptically, suggests that the cause of both is is that our solar system is beginning to drift into a possibly toxic zone of the universal ether.

Malone’s editorial assignment is fortunate, since he has just received a telegram from Challenger himself, summoning Malone to the scientist’s country home. The telegraph ominously tells him to bring oxygen.

When Malone arrives at the professor’s house, he finds that Challenger has arranged a reunion of the four South American adventurers: Challenger and Malone, as well as soldier of fortune Lord John Roxton, and Challenger’s scientific foil, the hyper-critical Professor Summerlee. Challenger confirms to them that the earth is about to pass through a toxic belt in the ether, which is certain to kill all life. But by remaining in Mrs. Challenger’s air-tight room with a few tanks of oxygen, this small group can remain alive just a little longer. Watching through the window, which looks out onto a nearby village, they will observe humanity’s end.

The Cosmos Is Not Our Friend

The central, fatalistic theme of the book is captured in a key metaphor proposed by Challenger in his letter to the London papers. Our planet, along with the others of our solar system, are like a handful of corks dropped into the Atlantic ocean:

The central, fatalistic theme of the book is captured in a key metaphor proposed by Challenger in his letter to the London papers. Our planet, along with the others of our solar system, are like a handful of corks dropped into the Atlantic ocean:

“The corks drift slowly from day to day with the same conditions all round them. If the corks were sentient we could imagine that they would consider these conditions to be permanent and assured. But we, with our superior knowledge, know that many things might happen to surprise the corks. They might possibly float up against a ship, or a sleeping whale, or become entangled in seaweed. In any case, their voyage would probably end by being thrown up on the rocky coast of Labrador…

“A third-rate sun, with its rag tag and bobtail of insignificant satellites, we float under the same daily conditions towards some unknown end, some squalid catastrophe which will overwhelm us at the ultimate confines of space, where we are swept over an etheric Niagara or dashed upon some unthinkable Labrador.”

In other words, the universe is a big, dangerous place, and we have no guarantee of safe passage.

As Challenger and his friends sit in the oxygen-saturated room, they watch people and animals outside fall victim to the poisonous ether, and discuss the meaning of the end of the world. Although physically these veteran adventurers are helpless, Challenger argues that mentally they should continue the fight until the end: “The ideal scientific mind should be capable of thinking out a point of abstract knowledge in the interval between its owner falling from a balloon and reaching earth.” Whether anyone will know or care about that point of abstract knowledge afterwards is something Challenger is not so sure about.

As Challenger and his friends sit in the oxygen-saturated room, they watch people and animals outside fall victim to the poisonous ether, and discuss the meaning of the end of the world. Although physically these veteran adventurers are helpless, Challenger argues that mentally they should continue the fight until the end: “The ideal scientific mind should be capable of thinking out a point of abstract knowledge in the interval between its owner falling from a balloon and reaching earth.” Whether anyone will know or care about that point of abstract knowledge afterwards is something Challenger is not so sure about.

As they await death, the characters discuss many questions whose previously well-accepted answers were now uncertain a the increasingly scientific age of Edwardian Britain. The discoveries of scientists from Darwin through Einstein had revealed a cosmos very different from the comfortably Christian one that had been taken for granted. (In fact, Einstein’s theory of relativity had already rendered obsolete the idea behind Doyle’s catastrophe scenario. The universal ether – a super-fine medium through which all light and matter moved – was no longer accepted as real.)

These discoveries are the implicit backdrop to the characters’ discussions. Will there be life after death? Will life evolve on earth again? Is human life not the purpose of creation? At one point, Professor Sommerlee challenges Challenger’s human-centric view of the cosmos:

“You seem to to take it for granted, Challenger,” said Summerlee, “that the object for which this world was created was that it should produce and sustain human life.”

“Well sir, and what object do you suggest?” asked Challenger, bristling at the least hint of Contradiction.

“Sometimes I think that it is only the monstrous conceit of mankind which makes him think that all this stage was erected for him to strut upon.”

It’s hard to maintain that conceit when on a beautifully clear day the entire human species faces sudden extinction.

The Narrow Path of Material Existence (SPOILERS)

Careful readers will note that right from the beginning, Malone’s narrative seems to be describing the earth’s passage through the poison belt as something that has already happened. Almost all end of the world stories are about the survivors, and The Poison Belt is no exception. As their last oxygen tank runs out, Challenger and his friends are ready to give themselves up to the poisoned ether. They smash the window to let in the outside air… and they find that the crisis has passed. They have survived.

Careful readers will note that right from the beginning, Malone’s narrative seems to be describing the earth’s passage through the poison belt as something that has already happened. Almost all end of the world stories are about the survivors, and The Poison Belt is no exception. As their last oxygen tank runs out, Challenger and his friends are ready to give themselves up to the poisoned ether. They smash the window to let in the outside air… and they find that the crisis has passed. They have survived.

In the last section of the book, they drive through London, now empty, silent, and littered with bodies. Their situation is now almost more awful than dying – what is their purpose now, the five of them in an empty world? It turns out that the answer is dealt with in yet one more plot twist that I won’t spoil.

Malone ends his narrative with the lesson to be drawn from the disaster of the poison belt: it is a “demonstration of how narrow is the path of our material existence and what abysses may lie upon either side of it.”

However, the abyss into which Europe plunged the year following The Poison Belt was one that humans dug for themselves.

Read more entries in my post-apocalyptic science fiction series, and my other science fiction reviews.

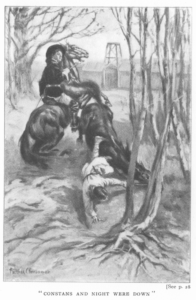

Image credits: Art from the original 1913 magazine publication of The Poison Belt from the Arthur Conan Doyle Encyclopedia, with original story illustrations by Harry Rountree. Cover, 1966 Berkeley Medallion edition by uncredited artist, from the Internet Speculative Fiction Database.

Filed under: Follies of the Human Condition Tagged: Post-apocalyptic, Science Fiction

We’re all familiar with classic scenes of a brutal post-apocalyptic world like this: A group of refugees from the pandemic is holed up in an abandoned building with a cache of food and arms, firing on a gang of assaulting raiders. Or, a former professor of English Literature, clad in goat skins and huddled around a fire, is telling his dirty, illiterate grandsons about life before civilization vanished.

We’re all familiar with classic scenes of a brutal post-apocalyptic world like this: A group of refugees from the pandemic is holed up in an abandoned building with a cache of food and arms, firing on a gang of assaulting raiders. Or, a former professor of English Literature, clad in goat skins and huddled around a fire, is telling his dirty, illiterate grandsons about life before civilization vanished. The storyline of The Scarlet Plague is straightforward. Professor James Howard Smith was once part of the social elite, as a member of the faculty of English Literature at the University of California, Berkeley. He’s now an elderly member of a primitive tribe that lives near the ruins of San Fransisco. Sitting around a campfire on an empty beach, he is telling his ignorant, abusive, and disbelieving grandsons about the world as it was sixty years earlier in 2013, right before the plague.

The storyline of The Scarlet Plague is straightforward. Professor James Howard Smith was once part of the social elite, as a member of the faculty of English Literature at the University of California, Berkeley. He’s now an elderly member of a primitive tribe that lives near the ruins of San Fransisco. Sitting around a campfire on an empty beach, he is telling his ignorant, abusive, and disbelieving grandsons about the world as it was sixty years earlier in 2013, right before the plague. Smith tells his grandsons about how things quickly fell apart in Berkeley. The first signs of total collapse were the severed bonds of kin and friendship that snapped when the symptoms of the plague appeared. The President of the Faculty turns Smith away from his office, knowing that Smith had been exposed to an infected student. Smith himself refuses to admit his own brother into his home when he sees the telltale blotches on his brother’s face. People try to escape the city, while gangs of armed looters engage in firefights in the streets.

Smith tells his grandsons about how things quickly fell apart in Berkeley. The first signs of total collapse were the severed bonds of kin and friendship that snapped when the symptoms of the plague appeared. The President of the Faculty turns Smith away from his office, knowing that Smith had been exposed to an infected student. Smith himself refuses to admit his own brother into his home when he sees the telltale blotches on his brother’s face. People try to escape the city, while gangs of armed looters engage in firefights in the streets. Of course Smith himself was the beneficiary of blind luck as well, and if anything, his education in English literature leaves him much less suited to survive in the present world than the chauffeur.

Of course Smith himself was the beneficiary of blind luck as well, and if anything, his education in English literature leaves him much less suited to survive in the present world than the chauffeur. The Scarlet Plague reminds us that, despite what we see as progress, our place in the world is still vulnerable. Technological progress may bring a better life, but it also masks the underlying structural weakness, and one day, the whole edifice may fail catastrophically. “All man’s toil upon the planet was just so much foam,” Smith tells us, washed away in the inevitable flood.

The Scarlet Plague reminds us that, despite what we see as progress, our place in the world is still vulnerable. Technological progress may bring a better life, but it also masks the underlying structural weakness, and one day, the whole edifice may fail catastrophically. “All man’s toil upon the planet was just so much foam,” Smith tells us, washed away in the inevitable flood. This review is part of

This review is part of  Back in 1805, the French priest de Grainville

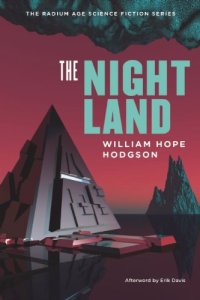

Back in 1805, the French priest de Grainville  This move of course required tremendously advanced technology, but now that technology is all but magic. The community’s survival depends on this inherited technology, but its secrets are lost, along with a rational view of the natural world. The twilight Night Land is filled with fearful mysteries and dimly perceived dangers: “The Giant’s Pit”, “The Headland From Which Strange Things Peer”, “The Road Where The Silent Ones Walk”, “The Watching Thing of the North-West,” and “The Thing That Nods.” Holed up in its bunker, humanity does little more than survive and look out on the lurid landscape.

This move of course required tremendously advanced technology, but now that technology is all but magic. The community’s survival depends on this inherited technology, but its secrets are lost, along with a rational view of the natural world. The twilight Night Land is filled with fearful mysteries and dimly perceived dangers: “The Giant’s Pit”, “The Headland From Which Strange Things Peer”, “The Road Where The Silent Ones Walk”, “The Watching Thing of the North-West,” and “The Thing That Nods.” Holed up in its bunker, humanity does little more than survive and look out on the lurid landscape. The young man’s adventure is a nightmare journey to the center of the earth. As in Jules Verne’s story, Hodgson’s hero finds a world that evokes the primeval past. There are strange geological phenomena and bizarre creatures who occupy a landscape that is no longer dominated by humans and their technology. At one point, the hero watches a band of “Humped Men” pursuing a giant creature, a scene that recalls Neanderthals attempting to take down a mammoth.

The young man’s adventure is a nightmare journey to the center of the earth. As in Jules Verne’s story, Hodgson’s hero finds a world that evokes the primeval past. There are strange geological phenomena and bizarre creatures who occupy a landscape that is no longer dominated by humans and their technology. At one point, the hero watches a band of “Humped Men” pursuing a giant creature, a scene that recalls Neanderthals attempting to take down a mammoth.  Something has to be said about the book’s famous flaws, which have doomed it to obscurity. I read the abridged version of HiLo Books’

Something has to be said about the book’s famous flaws, which have doomed it to obscurity. I read the abridged version of HiLo Books’  This review is part of

This review is part of  1912 was a good year for science fiction — according to some, it was

1912 was a good year for science fiction — according to some, it was  Brian Stableford

Brian Stableford  As I

As I  The human species is dying out and people know it. Except for some crop plants and a species of intelligent birds, humans are the only carbon-based life that remains. A deep-rooted fatalism has taken over. Suicide and euthanasia are common, and sometimes, when a community’s water runs low, required by law. People are generally willing to embrace death enthusiastically, since they have nothing to live for. Technology has eliminated the need for all labor, and “there was almost no work to be done.”

The human species is dying out and people know it. Except for some crop plants and a species of intelligent birds, humans are the only carbon-based life that remains. A deep-rooted fatalism has taken over. Suicide and euthanasia are common, and sometimes, when a community’s water runs low, required by law. People are generally willing to embrace death enthusiastically, since they have nothing to live for. Technology has eliminated the need for all labor, and “there was almost no work to be done.”  After the First World War, wrote historian Barbara Tuchman in her

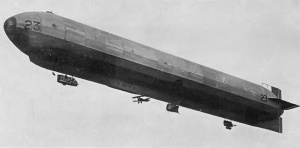

After the First World War, wrote historian Barbara Tuchman in her  The War in the Air tells the story of this “unexpected systole” through the eyes of Bert Smallways, an Everyman who stumbles into the center of war. Bert is “a vulgar little creature, the sort of pert, limited soul that the old civilization of the early twentieth century produced by the million in every country of the world.” He is an unsuccessful go-getter, living in the provincial, south English town of Bun Hill. As Bert moves from one failed venture to another, the world changes rapidly in the background. Traditional railways are replaced by that perennial symbol of misguided progress,

The War in the Air tells the story of this “unexpected systole” through the eyes of Bert Smallways, an Everyman who stumbles into the center of war. Bert is “a vulgar little creature, the sort of pert, limited soul that the old civilization of the early twentieth century produced by the million in every country of the world.” He is an unsuccessful go-getter, living in the provincial, south English town of Bun Hill. As Bert moves from one failed venture to another, the world changes rapidly in the background. Traditional railways are replaced by that perennial symbol of misguided progress,  Bert’s story is replayed again and again in subsequent post-apocalyptic fiction. Fortunately for us, two world wars didn’t lead to the total collapse of human civilization. But they were immediately followed by the threat of nuclear holocaust. And today, the potentially existential threat of catastrophic climate change raises the same question that drives these apocalyptic war stories: Can we ever control ourselves as well as we can control nature?

Bert’s story is replayed again and again in subsequent post-apocalyptic fiction. Fortunately for us, two world wars didn’t lead to the total collapse of human civilization. But they were immediately followed by the threat of nuclear holocaust. And today, the potentially existential threat of catastrophic climate change raises the same question that drives these apocalyptic war stories: Can we ever control ourselves as well as we can control nature?

You know how this turns out. The Canal goes ahead, disaster ensues, and the climate changes all over the world. England is plunged into a deep freeze. After some discussion and, as they say in movie ratings, mild peril, the British stiffen their upper lips and execute an orderly evacuation to Australia.

You know how this turns out. The Canal goes ahead, disaster ensues, and the climate changes all over the world. England is plunged into a deep freeze. After some discussion and, as they say in movie ratings, mild peril, the British stiffen their upper lips and execute an orderly evacuation to Australia. The Doomsman opens in what seems to be the primitive past: A young man sits on the shore of a bay, dressed in a tunic. In the forest behind him are the heavy wooden walls of a stockade, a clue to the defensive nature of life in this sparsely inhabited country. But not everything fits. The young man is looking across the bay at a vague, dark outline of some tall structure, while in his hands he holds a book: A Child’s History of the United States. He is sitting on the shores of New York, looking out at what’s left of Manhattan.

The Doomsman opens in what seems to be the primitive past: A young man sits on the shore of a bay, dressed in a tunic. In the forest behind him are the heavy wooden walls of a stockade, a clue to the defensive nature of life in this sparsely inhabited country. But not everything fits. The young man is looking across the bay at a vague, dark outline of some tall structure, while in his hands he holds a book: A Child’s History of the United States. He is sitting on the shores of New York, looking out at what’s left of Manhattan.

Like many later post-apocalyptic novels, the scraps of the last civilization’s technology have become an object for religious worship in the present one. In this case the technology is electricity, the secrets of which have been lost.

Like many later post-apocalyptic novels, the scraps of the last civilization’s technology have become an object for religious worship in the present one. In this case the technology is electricity, the secrets of which have been lost.