Ever been called a yeast sniffer? What would your reaction be? Shakespearean indignation?

Ever been called a yeast sniffer? What would your reaction be? Shakespearean indignation?

Blackguard! I challenge you to a duel.

Catholic guilt?

It was only once…in college…everyone else was doing it.

Sinful pride?

Damn straight. I’m growing some premo stuff right now.

For a distinct group of pastry chefs, sinful pride is the correct answer.

According to one of my culinary school instructors, there are two kinds of pastry chefs: plate jockeys and yeast sniffers. Plate jockeys are responsible for composed desserts at restaurants. Yeast sniffers fill bread baskets. There is very little crossover among professionals. I myself have primarily been a professional plate jockey; but I find few things more therapeutic than baking fresh bread. This one is for that little chef in all of us that likes to sniff a little yeast, if only recreationally.

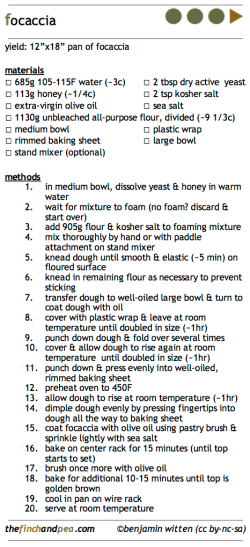

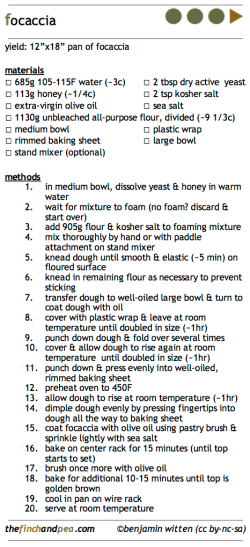

Click image for printable recipe card (PDF – 111kb)

The home bread baker faces two main road blocks: equipment and knowledge. Home ovens are not designed for baking bread. Commercial bread ovens generally use a stone base with the proper heat transfer for creating a crisp crust, releasing moisture, and allowing the appropriate rise. We can overcome this handicap with a few supplemental tools and our choice of bread. While I can’t install a bread oven in your home, I can share my baking knowledge – delicious, warm, fresh baked knowledge. Lets make some focaccia.

The Mix

I chose focaccia because it is (1) awesome! and (2) requires very little equipment – all we need is a baking sheet or a large cake pan. I fell in love with focaccia while living in Italy. The streets of Linguria1 are littered with bakeries making huge slabs of focaccia with toppings as simple as sea salt and olive oil or veritable meals of pesto, tomatoes, and anchovies.

Our first step in the making of focaccia, or any bread for that matter, is the mix. This is the stage at which you…wait for it…mix everything together. This is also the only stage of the bread making process where it is permissible to use your standmixer. We are going to start by dissolving our yeast in warm water between 105 – 115F, about the temperature of a warm shower. Yeast thrives at 95F, but dried yeast2 needs slightly hotter initial temperatures to activate. I also like to feed the yeast a bit of sugar or honey. Dried yeast includes some food, but I like to treat my yeast to a good meal before asking it to work for me.

The water should start to foam. This stage is called proofing – quite literally a proof of life. We are proving that our yeast is still alive by seeing if it processes gases. No foam means our yeast is dead. In that case, the only thing to do is hold a modest wake with plenty of beer and start over with new yeast. As we wait for our yeast to proof, we can stir all our dry ingredients (flour, salt, etc.) together. High concentrations of both salt and sugar can kill our yeast. So, we don’t want to have our salt and sugar just sitting on top of our flour when we pour in the yeast. Now that our yeast is a happily bubbling away and our dry ingredients are safely mixed, we can pour our yeast into the dry ingredients and mix them slowly with a wooden spoon or the paddle attachment on a standmixer.

As we mix, a few important things are preparing our dough to become a delicious loaf of bread. The yeast is spreading through the mix and feeding on both sugars and starches from the flour. Gluten proteins3 start to unfold as they come in contact with water. Finally, damaged starch in the flour absorbs water and swells into a structure on which our gluten network will form.

The Knead

Once all the ingredients are incorporated, it is time to get our hands dirty. The amount of kneading we do is the key factor in determining the final texture of our bread. As we knead, we unfold the glutens and slowly weave them together into a network, like threads in a piece of cloth, which is crucial for our bread’s structure. More kneading means a tighter weave, creating more stability and trapping more air. A hand-knit blanket has more give than an 800 count sheet because the blanket’s looser threads slide and stretch over each other. The sheet traps more air when thrown over a bed because the spaces between its threads are so small.

As we fold the dough and compress it, we create air pockets in the dough. The more we do this the smaller and more evenly distributed the bubbles become. The yeast will not create new air cells in the bread. They release gas too gradually for that. The yeast will only fill the air pockets that are already in the dough. It is up to us to make sure we are folding the dough over on itself as we knead it to create those pockets of air. Less kneading means fewer, larger air pockets and looser crumb4. More kneading means more, smaller air pockets and tighter crumb. This is why I banned mixers, including your bread machine. Standmixers, bread machines, and food processors do a great job when you are looking for a dough with a tight, cake-like crumb, because they knead so efficiently. If, however, you want less aerated dough for baguettes, ciabatta, sour dough, or focaccia, your machine will fail you. For softer, sticker doughs, like our focaccia, using a bench scraper5 can make this job easier and less messy.

We want to be sure we end up with the right amount of knead on our dough. Though most home bakers suffer more from under-kneading their doughs, it is possible to knead so much that we start to destroy the glutens and squeeze the water out of them, making a sticky mess. What we are looking for is “bounce back”. In soft doughs, like focaccia, it will not be as pronounced as in firm doughs. If we make a dimple in our dough with a finger, it should immediately start to spring back and remove the dimple.

The Ferment

And now we play the waiting game.

Once our dough is kneaded, we now have to let it rise. This is where we let the yeast take over. Yeast are single-celled fungi with about 1500 different species. Not all of those species will work for bread baking. We want “sugar yeast”6. Sugar yeast get their name from their food – sugars. The yeast consumes sugars (added sugars like honey or sugars from broken down starches) and converts them into carbon dioxide, alcohol, and a variety of flavor molecules. The sugar yeast used in bread baking produce more carbon dioxide and less alcohol than those used in brewing. That carbon dioxide fills the air pockets created by the kneading, makes your dough rise, and controls the final texture of the bread7. I once asked my brother the scientist, who happened to be studying yeast, to genetically engineer a strain of super yeast for baking. His reply was along the lines of:

That’s not really what I do. I work with the wrong kind of yeast, and I don’t trust that you won’t go all Captain Planet villain with your super yeast.

So, for now, we’ll have to settle for good, old-fashioned sugar yeasts.

Our dough is kneaded and ready to rise. Since we are diligent and following the recipe, we have or dough in an oiled bowl to prevent a crust from forming and have covered the bowl. At this point, many recipes say to place the bowl in the warmest spot in the kitchen and let it rise. They might even reiterate the 105–115F as the ideal temperature. Wrong! In fact, the colder the better. Active yeast, thrives at 95F, but that is not our ideal rising temperature. At 95F, the yeast is multiplying throughout the dough and puffing out carbon dioxide, but it is also producing sour by-products. At 80F, sugar yeast finds that perfect balance among multiplication, gas production, and the creation of pleasant tasting by-products. If time is not an issue, go colder. Colder temperatures slow the fermentation process. Our dough will take longer to rise, but we’ll get more flavorful by-products. I am a fan of refrigerator rising. Freshly kneaded dough may take 8-12 hours to fully rise in the refrigerator, but the flavor will be better.

In the focaccia recipe, we have two rises to increase the flavor output of the fermentation process. We intentionally added more sugar than in a traditional focaccia recipe to make sure the yeast has enough food for a second round.

Once our dough has doubled in size (size, not time, tells us when the rise is done), we punch it down. This is exactly what it sounds like. We are literally knocking the air out of the dough. Why spend all that time getting air into the dough if we are just going to punch it out? Fermentation is for flavor, not air8. If we don’t punch the dough down, those carbon dioxide filled air pockets in the dough will burst like balloons.

Once we’ve had our second rise, it’s oven time.

The Bake

As I said earlier, one of the great things about focaccia is that it is a pan bread. We don’t need equipment like baking stones or pizza peels. We just need to plop it into a sheetpan. For the sake of even baking, be sure to press you dough evenly into the pan. We are going to give it one last rise. This one is lets the air pockets start to fill. The dough should not double in size. If it does, our air pockets will rupture in the oven and your bread will collapse. The dough should look like it took a breath in.

Now comes the part that makes focaccia so sinfully delicious. We are going to press our fingers into the dough to make dimples and then coat the top with oil. Lots of oil. Pools of oil. The oil helps evenly distribute heat over the top of our focaccia to produce a crisp, brown crust and it soaks into the baking bread until every bite is dripping with delicious oil.

Once we our dough is in the oven, the bread is going to undergo changes in three stages. In the first stage, the increasing heat causes the yeast to become more active. This is when we see the bread rise-up in the oven, known as oven spring. In the second stage, the yeast die when the bread reaches 140F and the bread stops rising. The starches solidify (gelatinize) creating a support structure for the glutens. At 160F, the glutens coagulate and the structure of the bread is set. In the final stage, Maillard browning9 makes the crust crisp and brown and infuses the bread with characteristic toasted flavors. We add oil over the crust for a second time between the second and third stage to facilitate the browning reaction. Once we have that beautiful brown crust, we can check our loaf is done with a thermometer. Like meats, breads have internal doneness temperatures: 180-190F for soft breads and 190-200F for crusty breads.

The last step is the best. Cut off a piece of that bread, warm and fresh from the oven, and enjoy.

*Pastry recipes generally use masses, not volumes. It’s more accurate, and this is a science pub after all. When possible, I’ll also give volumes, but mass will yield better results. If you like to bake or do pastry, treat yourself to a kitchen scale.

CHEF’S NOTES

- Linguria is a region on the Northwest coast of Italy. Famous for the coastal cities of Cinque Terra, Linguria is also the birth place of pesto and Pinot Grigio.

- Most recipes use one of three types of yeast: instant, dry active, or cake. Our focaccia recipe and the post refer to dry active because that is the most common kind found in stores. Instant yeast does not have to be rehydrated before use, but provides less flavor to your food. Cake yeast provides more more flavor, but spoils quickly in the fridge. For greater longevity from your cake yeast, freeze it.

- Gluten is a protein found in the endosperm of wheat. Both whole wheat flour and white flour contain gluten, but the ratio of gluten in whole wheat flour is lower, because it also has the bran from the wheat in the mix. This is why whole wheat breads tend to be more dense. Less gluten, means less structure to trap air. The bread doesn’t rise as well and doesn’t have the strength to keep from collapsing on itself.

- Crumb refers to the interior of the bread. Tight crumb means that the air pockets are very small and evenly dispersed as in sandwich bread. Loose crumb means the air pocket are large and rather random throughout as in ciabatta. Tight and loose crumb have nothing to do with how soft the bread is. That is affected by the ratio of water in the recipe.

- A ridged plastic or metal tool generally used to scrape things off your table. Not unlike a putty or spackle knife.

- Bear in mind that I’m talking about yeast the way bakers talk about yeast. This is not the way Josh and Mike talk about yeast. They are probably rolling their eyes right now, because they are humorless pedants.

- Despite the fact that yeast leavened breads have been around for more than 6000 years, it wasn’t until Pasteur’s studies just over a century ago that we started to understand the leavening process.

- The pressure from the air does continue to knead and strengthen the gluten as well.

- A reaction between proteins and sugar under heat that creates browning and flavor. For more details see the post on making stocks.

I know what you are thinking. Ben makes the recipes he writes about sound easy. It seems like understanding the science behind what I’m cooking will help. But I can’t really make that. Can I?

I know what you are thinking. Ben makes the recipes he writes about sound easy. It seems like understanding the science behind what I’m cooking will help. But I can’t really make that. Can I?A frequent problem with both science protocols and cooking recipes is that the written procedure doesn’t let a non-expert (or anyone who wasn’t the person who wrote it) replicate the results. So, I tested Ben’s focaccia recipe using only what was written on the recipe card and present my results for your consideration. Well, your visual consideration. You’ll just have to trust me on the fact that it tastes A-MAY-ZING!