Editor’s Note – Thanks to Michele we now know that today is the inaugural UK Fungus Day. There was a Fungus Day last year, but it was confined to Wales and, therefore, was “National” Fungus Day (and in the minds of the English did not count anyway).

Ben first gave us this recipe over a year ago (18 September 2012) and we thought it would be a fitting tribute to a long overdue day in tribute to fungi.

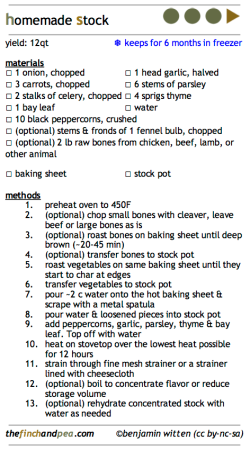

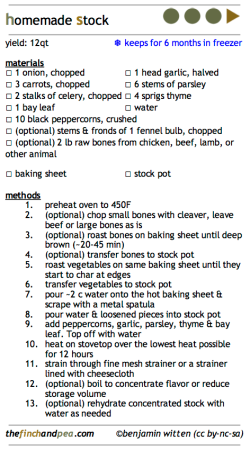

This week’s recipe is a bit of a two-for-one. The “main” recipe is a fall favorite of mine, mushroom soup (PDF – 770kb). This recipe only has five ingredients (not including salt and oil, which are staples, not ingredients), the most important of which is not, in fact, the mushrooms. It’s the stock (PDF – 115kb). Just replace the mushroom with any number of vegetables and we can still make a delicious soup – as long as we start with good stock. So, if we want to understand the science behind great mushroom soup, we need to understand the science behind good stock.

This week’s recipe is a bit of a two-for-one. The “main” recipe is a fall favorite of mine, mushroom soup (PDF – 770kb). This recipe only has five ingredients (not including salt and oil, which are staples, not ingredients), the most important of which is not, in fact, the mushrooms. It’s the stock (PDF – 115kb). Just replace the mushroom with any number of vegetables and we can still make a delicious soup – as long as we start with good stock. So, if we want to understand the science behind great mushroom soup, we need to understand the science behind good stock.

Click image for printable recipe card (PDF – 115kb)

The French use the term fonds, meaning foundation, when referring to stock. Anthony Bourdain has called it “the source,” as in “the source of all flavor”1. If you’ve ever been in a nice restaurant and thought, “This soup is so good” or “This sauce is amazing” or “Why doesn’t my rice taste this good at home?”, the answer is stock.

Let’s be clear. Stock is not that stuff you get in a box (or, god forbid, a dried-up cube of bouillon2). If you are heading to the store to buy stock for a recipe, you’ve already lost. If your recipe asks for “broth”, your recipe has failed you. Stock is made with bones. Broth is made with meat – meat that is rarely roasted, if it was even cooked at all before entering the stock pot. This is why store bought broth is pale and tastes like salty chicken skin. Bones carry more flavor than the meat, and browning them adds even more flavor, which will wind up in the water in our stock pot.

Click image for printable recipe card (PDF – 770kb)

Some chefs, especially the devotees to French cuisine a la Escoffier3, will waver a bit on this point. They claim that there is a place for “white stocks” made from unroasted bones in things like a white cream sauce to avoid discoloring the sauce. My answer to that: wrong!4

Stock should be brown. Period.5

Okay, semicolon. I will make an exception for fish stock. Fish bones should not be roasted. Roasting fish bones can burn the fish oils, which and creates overpowering and off-putting flavors. But if it doesn’t swim, it should be browned.

It’s all about flavor. Browning creates flavor. Stock made with browned bones has more flavor. Food made with stock made with browned bones has more flavor. Making a cream sauce with white stock sacrifices flavor for aesthetic – pearly white and bland. In my opinion, good food tastes good. Since we know we want flavor, let’s find out how that flavor is created.

The Browning

We owe much of the developed flavor in our meats and vegetable to a simple application of heat, and the complex and varied reactions it causes. When we see our meats, fruits, and vegetables browning, what we are really witnessing is either caramelization or Maillard browning. Most people are familiar with caramelization from…well…caramel. Gooey, sweet, delicious caramel. When sugars are exposed to high heat, the molecules break down and recombine to form new products. Some of those products include brown-colored polymers, organic acids, and fragrant, volatile molecules. Even a simple sugar like glucose6 can generate over 100 different products during the caramelization process. The combination of fragrances, acids, and flavor molecules makes caramel complex and delicious.

Maillard browning, put simply,  is caramelization of proteins. Instead of the protein denaturing and recombining into a variety of units, amino acids in the protein react with sugars in meat or starches in vegetables. This reaction creates an unstable structure, which breaks down into a wide-range of by-products, including brown-colored polymers. Because those brown polymers are always present alongside the flavor molecules, chefs can operate according to a simple equation:

is caramelization of proteins. Instead of the protein denaturing and recombining into a variety of units, amino acids in the protein react with sugars in meat or starches in vegetables. This reaction creates an unstable structure, which breaks down into a wide-range of by-products, including brown-colored polymers. Because those brown polymers are always present alongside the flavor molecules, chefs can operate according to a simple equation:

Browning = Flavor

It is important to note when attempting to create browning that both caramelization and the Maillard reaction require high temperatures. Caramelization begins around 310F (154C). In the case of Maillard browning, the hotter the better. Maillard browning needs higher temperatures than caramelization to create the maximum amount of flavor and aromatic molecules. Consider two identical steaks in two identical pans on two identical stove tops. The first steak goes into a cold pan that subsequently heats up. The second steak goes into a very hot pan. The second steak will always taste better and have a better sear on it. That sear is the result of the Maillard reaction. Contact with a well heated surface lets the maximum amount of Maillard browning to occur as fast as possible. As the first steak slowly heats it loses some of its capacity for Maillard browning, because at lower temperatures the proteins are bond to each other leaving fewer available proteins to join the wild, molecular toga party that is Maillard browning.

For our stock, we are relying on the processes of caramelization and Maillard browning for our flavor. Instead of adding raw or unbrowned foods with the limited flavor and odor molecules that the product naturally contains, we add browned food with its menagerie of tasty molecules. I recommend using an oven set around 400F (204C) . The oven provides uniform heat all around the food for even and complete browning. We can brown in a pan on the stovetop, but the heat only comes from one direction. This leads to either uneven browning or a lot of work ensuring the we brown all of your food.

The Deglazing

DO NOT forget to deglaze. If you do, I will find you and I will slap you.

Deglazing is the use of a liquid to remove brown food residue from a pan. Water soluble molecules produced in our browning reactions lift off the pan as the liquid rapidly evaporates off the hot surface. Liquids containing alcohol, like wine, do a better job of deglazing than water because the alcohol evaporates faster, pulling away more residue with it. For our purposes, water will do just fine. We want flavor. Those brown bits on the pan are the products of browning reactions. We definitely want that in our stock. Deglaze, or face my fists of fury.

The Steeping

Steeping is  the easiest part of making stock. At this point, we have our roasted bones and veggies in a stock pot along with the water left over from deglazing. We’re going to add some herbs, garlic and peppercorns. This is a great way to use up any herbs in the fridge that are starting to look a bit sad. Fill the pot with water, place it on the burner over your lowest heat setting, and walk away. All those complex flavor and odor molecules that we worked so hard for will slowly dissolve into solution in your water, we don’t have to do a thing. To make sure you get the maximum amount of flavor out of your stock, I recommend letting it sit on the heat for 12 hours.

the easiest part of making stock. At this point, we have our roasted bones and veggies in a stock pot along with the water left over from deglazing. We’re going to add some herbs, garlic and peppercorns. This is a great way to use up any herbs in the fridge that are starting to look a bit sad. Fill the pot with water, place it on the burner over your lowest heat setting, and walk away. All those complex flavor and odor molecules that we worked so hard for will slowly dissolve into solution in your water, we don’t have to do a thing. To make sure you get the maximum amount of flavor out of your stock, I recommend letting it sit on the heat for 12 hours.

In my experience, people get anxious about cooking processes, like steeping, that are not active. They have a lot of questions about steeping. Fortunately, I have just as many answers:

- No, your water will not evaporate away. Depending on your stove, you may lose between 2-4 inches of water, but that is not a problem. In fact, the more you let it cook down, the more concentrated the flavor will be.

- Yes, I said 12 hours. The easiest way to do this is to make stock in the evening and let it sit on the heat overnight. And no, you will not burn your house down, assuming that you don’t store kindling or gasoline on the stovetop. If you do leave flammables on the stovetop…well I’ll refer you to some of the biologist in this pub for a discussion on natural selection. Most restaurants make stock this way to save cooking space. A restaurant is more likely to burn down from an electrical or heating system fire than a stock pot steeping overnight.

- Yes, your house will smell delicious. I get “that smells great, what are you cooking?” more often when cooking stock than anything else. Beware, the smell could attract bands of roving gourmands, neighborhood busy-bodies, and, of course, land-sharks. You’ve been warned.

After 12 hours, we strain the stock to remove the bones and vegetables, which we will discard, as they are now flavorless. They gave every last drop of tasty in the service of our stock and, thanks to their sacrifice, we now have a pot full of foundation for some simple and flavorful food, like mushroom soup (PDF – 770kb).

CHEF’S NOTES

- Though sometimes Bourdain can seem to be mostly a TV personality and what he says for shock value, he knows food and I have to agree with him on this one – and not just because I’m afraid he’d beat the crap out of me if I didn’t.

- Bouillon is just the French term for broth. It may sound fancier, but it is no better than its American counterpart.

- Auguste Escoffier (1846 – 1935) wrote a cookbook called Le Guide Culinaire, which changed the face of haute cuisine in Europe by revitalizing and simplifying much of classic French cuisine. Escoffier is often thought of as the father of modern French cuisine.

- This not science, just my opinion…but I’m right.

- Not totally sure how to punctuate after exclaiming “period.” A period seems redundant and an exclamation point seems an oxymoron. Any advice from english teachers out there would be much appreciated.

- Granulated sugar is a disaccharide, meaning it is made up of two bonded sugars, glucose and fructose.

Filed under:

From the Kitchen Tagged:

Fungus,

fungus day,

Mushroom Soup,

mushrooms,

Soup,

Stock

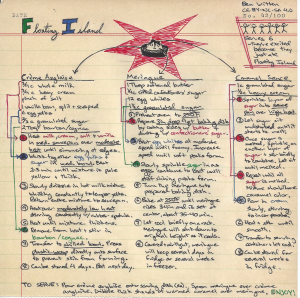

Floating island is why I am a chef. My father, who is an exceptional cook*, was always in charge of preparing our special occasion meals. Christmas dinner, friends coming over, celebrations – he would turn out some kind of delicious feast without fail. On one such occasion, when a boss was joining us for dinner, my dad once more set off to pull out all the stops. In this instance, the boss happened to have a sweet-tooth. So, in order to pluck at his food soft spot, my dad decided to making floating island for dessert. The dinner preparation was a large undertaking so he enlisted my help. At 12, I would have been just about the right age to start an old world kitchen apprenticeship. In a life changing moment, he slid his copy of

Floating island is why I am a chef. My father, who is an exceptional cook*, was always in charge of preparing our special occasion meals. Christmas dinner, friends coming over, celebrations – he would turn out some kind of delicious feast without fail. On one such occasion, when a boss was joining us for dinner, my dad once more set off to pull out all the stops. In this instance, the boss happened to have a sweet-tooth. So, in order to pluck at his food soft spot, my dad decided to making floating island for dessert. The dinner preparation was a large undertaking so he enlisted my help. At 12, I would have been just about the right age to start an old world kitchen apprenticeship. In a life changing moment, he slid his copy of  Julia Child’s The Way to Cook over to me and pointed to the recipe. I could practically hear Julia’s voice speaking from the pages as she told me that I “must have courage” in preparing the crème anglaise. To this day, that book is sacrosanct among my cooking library.

Julia Child’s The Way to Cook over to me and pointed to the recipe. I could practically hear Julia’s voice speaking from the pages as she told me that I “must have courage” in preparing the crème anglaise. To this day, that book is sacrosanct among my cooking library.

THE EGG

THE EGG