VTR – Barrel-Aged Manhattan by Edsel Little (CC BY-SA 2.0)

If you were wondering what to drink while you watch Manhattanhenge, the choice is obvious – a Manhattan, preferably barrel-aged.

As I grew into manhood, my father promoted a strong set of core values in me – politeness, gratitude, compassion, kindness – as well as respect for a good glass of whiskey and Winston Churchill. What, you may ask, does Winston Churchill have to do with this classic whiskey cocktails and science? Glad you asked.

The most common Manhattan origin story states that it was created in 1874 at New York’s Manhattan club for a banquet hosted by Lady Randolph Churchill, Winston’s mother. That was the same year Winnie was born. I doubt he, of all people, would discourage the notion that helping coordinate the creation of the Manhattan cocktail in utero may have been early practice for coordinating the Allied victory in WWII. At the very least, the Manhattan and Winston are akin to each other. Watch out Jagermeister!

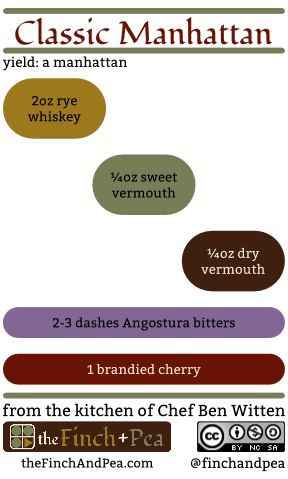

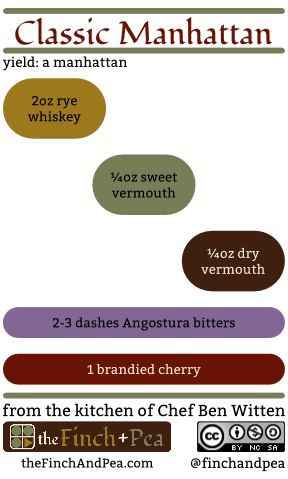

Classic Manhattan (Click Image for PDF – 73kb)

The classic Manhattan recipe is a fairly simple.

I am not going to delve into the creation of distilled spirits. We’ll save that for another post in favor of different food science matters today, but I do want to quickly touch on the composition of the recipe.

For the whiskey, you can use others besides rye. At the time that the Manhattan was invented, rye whiskey was the most commonly found and used whiskey in New York. I personally tend to use Bourbon whiskey (ie, corn).

For the vermouth, the measures I gave are technically for a “perfect” Manhattan. You can make a Manhattan just as well with only sweet or only dry vermouth. I have even had great Manhattan’s made with other sweet fortified wines like port and Lillet instead of vermouth.

For the bitters, “Angostura” is a brand name of aromatic bitters. Use any aromatic bitters you like, but make sure they are of good quality, because they can significantly affect the taste of your cocktail. My personal favorite are bitters from the Fee Brothers.

For the cherry, it is completely and absolutely unacceptable to use a maraschino cherry. Ever. In any cocktail. A maraschino cherry is, usually, a Queen Anne or Ranier cherry that has been bleached then placed in a mixture of salt, sulfur-dioxide, corn syrup, and food coloring - an ingredient list that contains only one item that should be going into your food (or drink). Use brandied cherries or amarena cherries.

So, now that we know how to make a solid Manhattan, let’s start playing around with it.

Barrel-Aged Manhattan1 (Click Image for PDF – 84kb)

Showing Its Age

Featuring a house barrel-aged cocktail has become a trend among artisan cocktail bars. Charging more for house barrel-aged cocktails has also become a trend. We might not question the price increase since “barrel-aged” sounds expensive. The reality is that barrel-aging a cocktail costs no more than an extra 75 cents per cocktail. What we are paying for is the experience of added deliciousness.

“How,” you may ask in perfectly timed foreshadowing, “does the barrel-aging create said deliciousness?” As for that…bring on the science!

The scientific community has been sadly remiss (some might even say negligent) in doing any direct research on aging cocktails, we are going to extrapolate from what we know about barrel-aging wine and spirits. When wine and spirits are barrel-aged three main processes – oxygenation, flavor extraction, and change in body – and time.

Oxygenation

Oxygen is highly reactive. We see this very starkly in many areas of food. How can the flesh of a freshly cut apple brown in a matter of minutes? Oxygenation.

Like many things in food, oxygenation can be a good or bad thing. It depends on dose and context. Vinophiles will be familiar with the idea of aerating wine, either by swirling the glass, letting a wine “breathe,” or pouring it through an aerator. The mixing of oxygen into the wine builds flavor as the oxygen reacts with molecules in the wine. In the short-term, this can improve the flavor and complexity of the wine.

Leave that same wine sitting open for two days and the flavors will have degraded. The oxygen will have continued to react with the molecules in the wine. It will have had so many opportunities to interact with the flavor molecules in the wine that the pleasant flavor is destroyed.

Our cocktail will not be exposed to unlimited supplies of oxygen in the barrel. There is very little oxygen interaction once the cocktails are inside the barrels, but there is some. We often call this micro-oxygenation. How will that affect our barrel-aged Manhattan?

Our Manhattan will generally contain some kind of fortified wine (i.e. vermouth, port, Lillet), which will develop flavor from the micro-oxygenation. Furthermore, oxygen will convert some of the ethanol into acetaldehyde, which has apple, grass, and nutty aromas. Acetaldehyde can further react with the oxygen to become acetic acid (the acidic component of vinegar). Acetic acid can add depth of flavor in small quantities, but can become harsh in excess.

In the end, our barrel-aged cocktails will develop additional depth of flavor from oxygenation of the fortified wine components as well as the creation of acetaldehyde and small amounts of acetic acid.

Flavor Extraction

The flavor extraction component is perhaps the simplest to understand. Any liquids sitting in a barrel are going to pull out water-soluble flavors from the components of the barrel over time. The most notable of these is vanillin. Vanillin is the main flavoring component of vanilla extract, but vanillin can be found as a naturally occurring component in a wide range of things, including olive oil, raspberries, coffee, oatmeal, maple syrup, and (you guessed it) oak barrels. Due to its complex flavoring, the vanillin that leaches from the barrel staves into the cocktail imparts subtle flavors of spices, earthiness, tobacco, flowers, and a mishmash of flavors that we often refer to as “oaky”.

Heaven Hill Warehouse by Shannon Tompkins (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Different barrels allow us to pull out additional flavors. Toasted barrels, like those used in whiskey production, add smokiness as well as more complex flavor molecules generated by heating and burning the wood.

We also extract residual flavors from anything that was previously stored in the barrel. Just as the liquid in a barrel absorbs flavors molecules from the barrel, the barrel absorbs flavor molecules from the liquid. There are many regulations that dictate how many times a barrel can be used for the production of a specific types of wine or spirits2. Often a barrel can only be used once. Those barrels are often reused for other purposes. Brandy is often aged in old wine barrels. Beers aged in whiskey barrels pick up subtle whiskey notes. And, if you ever have the chance to try maple syrup aged in old wine barrels, you definitely should not pass up the opportunity.

Change in Body

Barrel-aged cocktails drink smoother than usual. There is research that speaks to the processes that create smoothness in alcohol solutions inside a wood barrel. “Oak Wood Hemicelluloses Extracted with Aqueous–Alcoholic Media” by Pisarnitskii, Rubeniya, and Rutitskii (2006) states that an acidic liquid creates a partial breakdown of hemicellulose (a component of white oak), which increases the content of the sugars glucose, fructose, xylose, and arabinose in the liquid. This is what creates more body and greater smoothness in barrel-aged liquids. It further states that lower alcohol content also leads to higher hemicellulose extraction.

Wines are generally more acidic than spirits and lower in alcohol content, which means that wines will develop smoothness and body faster than spirits. We see proof of this in actual production. Most good, barrel-aged wines are aged 1-2 years. Many of the best quality bourbons are aged more than 4 years. What does this mean for our aged cocktails?

Our Manhattans contain fortified wine. They will tend to be more acidic and lower in alcohol content than the spirits alone. We should expect a higher rate of hemicellulose extraction leading to a more rapid development of smoothness and body.

Now that we know the benefits of barrel-aging, how long should we age our Manhattan?

Size Does Matter

The speed of the aging process depends on the size of the barrel. This is, quite simply, a matter of wood exposure. Surface area increases by the square. Volume increases by the cube. The smaller the barrel, the greater the ratio of surface area to volume. In other words, in a smaller barrel, more of your cocktail is touching the sides of the barrel, which is necessary for flavor extraction and developing body.

In the United States, whiskey is aged in 53-gallon barrels. A 53-gallon (233.5 liter) barrel is roughly 21-in across and 36-in tall, providing is about 3065in2 (19480cm2) of direct contact between barrel and liquid. A 1-liter barrel, which is what I use to age my cocktails, is roughly 4-in across and 6-in tall, providing about 100inch3 (640cm2) of direct contact between barrel and liquid. A 1-liter barrel gives us almost eight times more direct contact with the barrel per liter of liquid (640cm2/L) compared to a 53-gallon barrel (84cm2/L).

This increased exposure exponentially decreases the aging time. For example, we can (and I have) age our own whiskey at home in a barrel. I have found that I can take a white dog whiskey2 and age it to a smooth, deep, complex bourbon in a5 weeks in a 1-liter barrel. The same process would require at least 2 years in a 53-gallon barrel. Although using smaller barrels would speed up the aging process for the US whiskey industry, it is more cost-effective for companies to use larger barrels4.

For our Manhattan, about 10 days in a 1-liter barrel gives me excellent results.

It’s a Hard Job, But Somebody Has to Do It

Now that we have talked about the science that goes into barrel-aging a Manhattan (or anything else for that matter), I want to leave you with some final advice in crafting your own barrel-aged cocktails.

Remember that low alcohol and high acidity will age faster. The cocktail will get sweeter and smoother as it ages, so err on the less sweet side. Be careful about adding too much fruit juice and the like into your aged cocktails — if the ABV% drops below 15% you start growing bacteria. Most importantly, taste throughout the aging process, so you know when your cocktail is right for you. I also like to save a small bottle of the original cocktail for comparison tasting at the end of the aging.

Well, I think I’m all scienced out now. I could use a drink.

NOTES

1. To make your own vanilla and orange tinctures, place either a scraped vanilla pod or orange zest in a small bottle, top with brandy and let sit for 2-4 weeks shaking occasionally.

2. These rules are usually driven by style and creating identifying features for a type of wine or spirit.

3. The name often given to whiskey before it has been aged. White dog has increased in popularity and can be readily found online or in many liquor stores.

4. Oak is expensive and it cost less to make fewer, larger barrels, especially since some barrels are only used once for aging whiskey.

Filed under:

From the Kitchen Tagged:

cocktail,

food science,

liquor,

manhattan