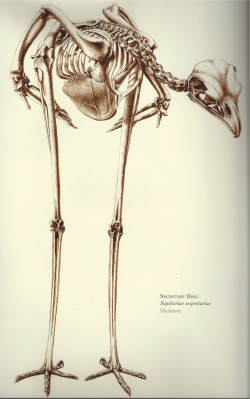

Skeleton of a Great Hornbill by Katrina von Grouw – The Unfeathered Bird (2012 Princeton University Press – Used with Permission)

Katrina van Grouw’s The Unfeathered Bird is curious hybrid – not a textbook, not quite an art book. Forget definitions, it is a rich and beautiful work with many rewards for readers.

I approached this book as a visual artist and a decidedly non-expert reader, and I will admit an initial bias against it. I love color. I was convinced that a coffee-table book of birds drawn without their feathers was like a book on ice cream that featured only the cones.

I was wrong.

The Unfeathered Bird is not only highly informative, in a straightforward and fairly jargon-free way, it is also gorgeous. Although van Grouw provides an amazing amount of detail about the insides of birds – in particular their skeletons – she says that “this is really a book about the outside of birds. About how their appearance, posture and behavior influence, and are influenced by, their internal structure.”

Van Grouw opens with a general introduction to the common anatomical features of birds, and then moves on to six sections about different orders of birds (Picae, Gallinae, etc), which in turn are broken down into chapters about bird families, ranging from pigeons to penguins to pelicans.

She says that took about 25 years to produce, and it looks it. Van Grouw, whose background encompasses fine art, taxidermy and curating museums’ bird collections, has brought all her expertise to bear on these pages. The 385 Illustrations – mainly of skeletons, some of skinned birds – were all done from actual specimens, either collected by van Grouw and her friends or from museum collections.

The cream-colored pages, sepia-tinted pencil drawings, and hand-drawn fonts give the book the look of a timeless classic.

The first section of the book shows the common features of birds, including beautifully detailed drawings of how feathers and muscles are attached to wings to enable flight. As she moves on to specific families of birds, the illustrations focus on the differences in such features as claws, beaks, necks, and eye sockets.

Van Grouw pays a great deal of attention to how the anatomy of various birds is adapted to different environments – whether birds grasp tree branches, swim in the ocean, or walk in tall grass, for example. Her highly detailed pencil drawings show the vast variety of beaks, wings, feet, and claws – from tiny swallows to giant ostriches. One detail that amazed me – owls that hunt in the forest have special feathers for silent flight, while owls that hunt fish do not, because their prey can’t hear them.

Red-and-Green Macaw – Katrina van Grouw – The Unfeathered Bird (2012 Princeton University Press – Used with Permission)

Many of the birds are depicted in action, flying, swimming, or even grasping prey. Because of their lack of feathers, this does sometimes look a bit odd. A skinned Macaw grasping a perch with one claw and a pencil with the other (p.56) looks quite uncanny, as do the ducks in flight (pp 94-95), which look a bit like Christmas dinner trying to escape.

On the whole, though, the book is full of visual delights. If I had to pick a single image that sums it up, Van Grouw’s rendering of an ostrich skeleton (p 229) is a tour de force, both exquisitely detailed and powerfully dramatic.

The Unfeathered Bird is itself a unique specimen. While it’s sure to be treasured by bird-lovers, it has much to offer to readers who don’t know a grebe from a loon.

Other perspectives from THE FINCh & Pea:

Rebecca Heiss: The Birds of The Unfeathered Bird

Josh Witten: The Layers of The Unfeathered Bird