Season's greetings!

For Christmas last year in this blog we had a

Network analysis of McDonald's fast-food, in which I examined the food nutrient content of a well-known fast-food vendor. This year I continue the same theme, but expand it to cover an analysis of the geographical locations of various fast-food chains within the USA.

The US restaurant industry included about 550,000 restaurants in 2012 (

SDBCNet). Technically, this food industry distinguishes different types of restaurant. The ones we are interested in here are called "quick service restaurants" (QSR), which includes what are known as fast-food and fast-casual restaurants. These are sometimes also called "limited service restaurants".

There are quite a few QSR companies in the USA, and each of them has quite a few locations. In 2012, there were apparently 313,000 fast-food and fast-casual restaurants (Yahoo Finance blog

The Exchange), which is more than 50% of the total restaurants. In 2005, more than two-thirds of the largest 243 cities in the US had more fast-food chains than all other restaurant types combined (

Zachary Neal).

The QSRs serve an estimated 50 million Americans daily (

The Statistic Brain). Indeed, in a 2011 poll of people in 87 U.S. cities, there were several places where >30% of the people had visited QSRs 20+ times in the previous month (nearly once per day), while in all cities >80% of the people had visited at least once (

Sandelman & Associates).

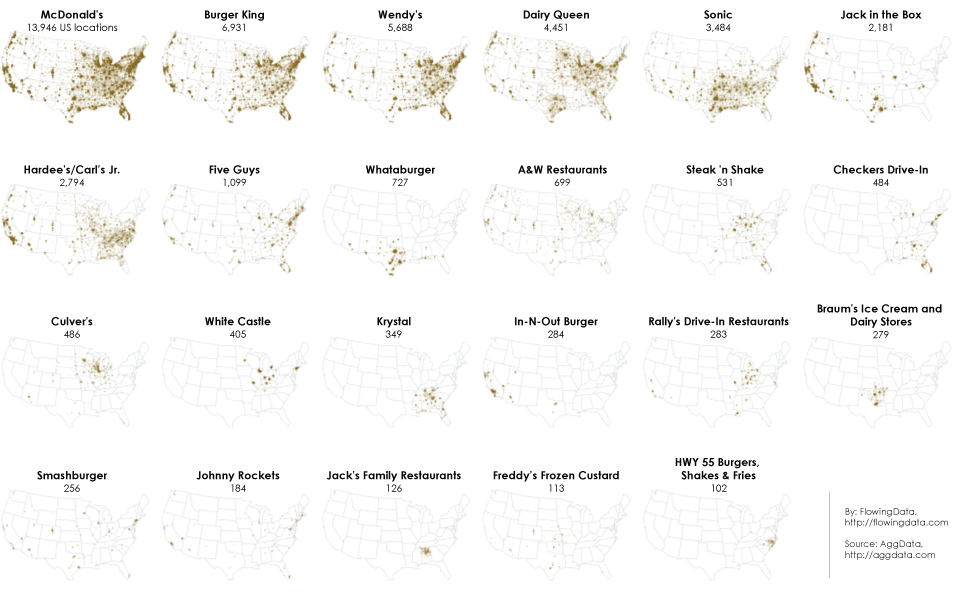

The

QSR group reports that the national top 20 fast-food chains for 2012 were as shown in the first graph. This includes both company-owned units as well as franchised locations. Note that McDonald's had 34,480 restaurants in its worldwide system, with 14,157 of those being in the USA (

The Exchange).

It is of interest to look at how this pattern has changed through time, and so I have taken the data from the QSR group's reports for 2003 to 2012, inclusive (these are the only ones available online). These data are for the number of locations of each of the top 50 chains each year in terms of dollar income. There are 61 chains that appear in the list for at least one of the years, but only 46 of these appeared often enough in the top 50 to be worth including in the analysis.

For this analysis, we can use a phylogenetic network. As usual, I have used the manhattan distance (on range-standardized data) and a neighbor-net network. The result is shown in the next figure. Fast-food chains that are closely connected in the network are similar to each other based on their restaurant numbers over the past decade, and those that are further apart are progressively more different from each other.

The network forms a simple chain from Subway (the biggest) through to the group of very similar-sized chains at the bottom-left. This indicatess that most of the restaurant chains have been fairly consistent in their relative sizes throughout the past decade (ie. the big stayed big and the small stayed small), although some chains have changed size. For example, KFC and Taco Bell have each shrunk by 15% since 2007, while Jack in the Box has expanded by 10%.

However, there is a large reticulation in the network involving Starbucks. This is caused by the fact that Starbucks started the decade as a much smaller chain than both Burger King and Pizza Hut, but it is now much larger than either of them. Similarly, there is another reticulation involving Cold Stone Creamery, which expanded rapidly in 2005 (increasing their number of locations by 50%).

The number of locations does not relate directly to dollar turnover, of course, as Subway has much smaller restaurants than do most of the other chains. In this respect, McDonald's leads the way by a considerable margin, with $35,600,000,000 in system-wide sales in the USA during 2012, versus $12,100,000,000 for Subway. This works out at $2,600,000 and $481,000 per restaurant per year, respectively. Starbucks comes in third, with $10,600,000,000 in 2012 ($1,223,000 per unit).

However, let's stick to the number of units, rather than the dollars, and consider their geographical locations. There are several datasets available on the internet that provide this information for different chains (which you actually could get yourself by visiting the homepage of each chain and asking for the location of each restaurant, one at a time!). If you are prepared to pay some money, then you can have the latest list from

AggData; but I am not in that league.

However, apparently the man at the

Data Pointed blog is in that league, or was in 2010. His mapped version of the data for McDonald's (only) looks like this next figure (each dot represents one restaurant).

This has led him to contemplate the

McFarthest Point, which is the point in the contiguous US states that is furthest from a McDonald's restaurant. He reckons that its map co-ordinates are: +41.94389, –119.54010. He has made an excursion to this spot (along with some fast-food), which you can read about in

A Visit To The McFarthest Spot.

In turn, this caused the man at the

Consumerist blog to contemplate the equivalent spot for Subway. This is currently estimated to be +42.397327, –117.956840 (

Is This the Farthest Away You Can Get From a Subway in the Continental U.S.?).

Returning now to the data sources, you could also look at the data from the

Food Environment Atlas (by Vince Breneman and Jessica Todd, of the USDA Economic Research Service). At the time of writing, this contains a

Map with Fast-food restaurants / 1000 population for 2009, showing each individual county. This refers to the total number of units, summed across all fast food chains. A similar map is available at

Business Insider, aggregated by state (but based on the 2008 data).

However, I cannot pay for the data, and I want the data separately for the different fast-food chains. That leads me to the

Fast Food Maps by Ian Spiro. In 2007, he scraped the data from the web pages of various chains (as I noted above), and has made it available as a web page and an associated datafile.

He has included data for 10 of the fast-food chains, based on those present in the state of California. So, he covers only 8 out of the top 20 national chains: McDonald's, Burger King, Pizza Hut, Wendy's, Taco Bell, KFC, Jack in the Box, and Hardee's. To these, he adds Carl's Jr (mainly on the West Coast of the USA) and In-N-Out Burger (mainly in the South-West), which I did not include in my analysis.

To analyze these data, I took the information for each chain in each state and divided this by the number of people in that state (to yield the number of restaurants per 100,000 people per chain per state). I then produced a phylogenetic network, as described above, and as shown in the next graph. States that are closely connected in the network are similar to each other based on the density of restaurants of each chain, and those that are further apart are progressively more different from each other. I have color-coded the states to highlight the similarities.

In the network, the states turn out to be arranged roughly geographically, with a few exceptions. In other words, neighboring states have similar densities of restaurants from certain fast-food chains.

For example, the red-colored states are from the West (including in the Pacific!), and they don't have Hardee's, but do have most of the Jack in the Box restaurants. The brown-colored states are from the North Centre, and these have the highest density of Burger King and Pizza Hut. Montana is separate from this grouping because it has a lower density of both Burger King and KFC.

The orange-colored states are from the Mid West and the South, and these have the highest density of Hardee's. Georgia is separate from this grouping because it has a lower density of Hardee's; and Florida is separate because it has a lower density of most chains. The blue-colored states are also from the Mid West, and these have the highest density of McDonald's and Wendy's. Illinois is separate because of a lower density of most chains (particularly KFC) except for McDonald's.

The dark-green-colored states are from the North East, and these don't have Hardee's, and they have the lowest density of Pizza Hut. The light-green-colored states are also from the North East, and these form a separate grouping because they have a higher density of most chains except McDonald's. Maryland is separate because it has an even higher density of most chains (particularly Hardee's); and Delaware has a higher density of Hardee's and Taco Bell.

Finally, Oklahoma and New Mexico have the highest density of KFC.

NB. For an interactive map showing the locations of the 507 Dunkin' Donuts, 269 Starbucks and 235 McDonald's in New York City (in October 2013), check out

Mapping the Big Apple's Big Macs, Coffee, and Donuts. The concentration of Starbucks in downtown and midtown Manhattan is truly impressive. Indeed, 43% of the city's cafés are either Dunkin' Donuts or Starbucks (

Coffee and Tea in New York City).

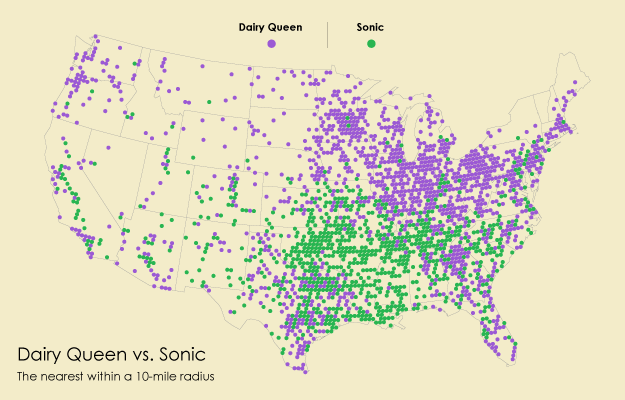

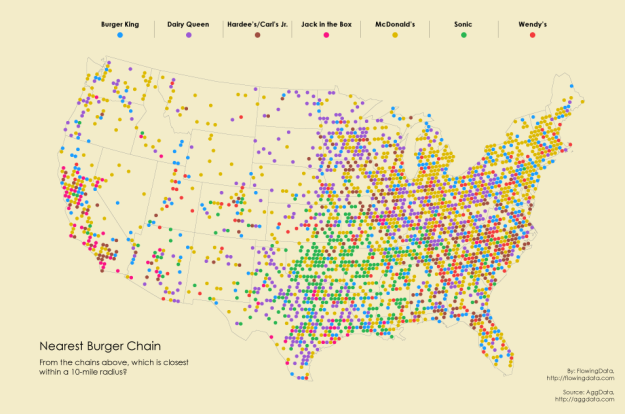

ConclusionSo, there you have it — fast-food is not randomly distributed in the USA. Where you live determines how much you have available of the different types. Indeed, as

Pam Allison's Blog notes: "Although restaurants like McDonalds are very popular nationwide, they aren’t necessarily the most popular on a local level. In fact, there are only a handful of zip codes in the United States where McDonald's is the most popular. Rather, many local or regional chains are the more likely choice with consumers."

There are many other aspects to the geography of food, especially fast-food; but these can wait until a later blog post.