This is a joint post by David Morrison and Guido Grimm

Over a year ago, we

showed a network relating to the World Happiness Report 2018 based on the variables used for explaining why people in some countries report themselves to be happier than in other countries. A

new WHR report is out for 2019, warranting a new network.

The 2019 Report describes itself as:

a landmark survey of the state of global happiness that ranks 156 countries by how happy their citizens perceive themselves to be. This year’s World Happiness Report focuses on happiness and the community: how happiness has evolved over the past dozen years, with a focus on the technologies, social norms, conflicts and government policies that have driven those changes.

For our purposes, we will simply focus on the happiness scores themselves. So, this time we will base our analysis on the country rankings for the four measures of subjective well-being:

- Cantril Ladder life-evaluation question in the Gallup World Poll — asks the survey respondents to place the status of their lives on a “ladder” scale ranging from 0 to 10, where 0 means the worst possible life and 10 the best possible life

- Ladder standard deviation — provides a measure of happiness inequality across the country

- Positive affect — comprises the average frequency of happiness, laughter and enjoyment on the previous day to the survey (scaled from 0 to 1)

- Negative affect — comprises the average frequency of worry, sadness and anger on the previous day to the survey (scaled from 0 to 1)

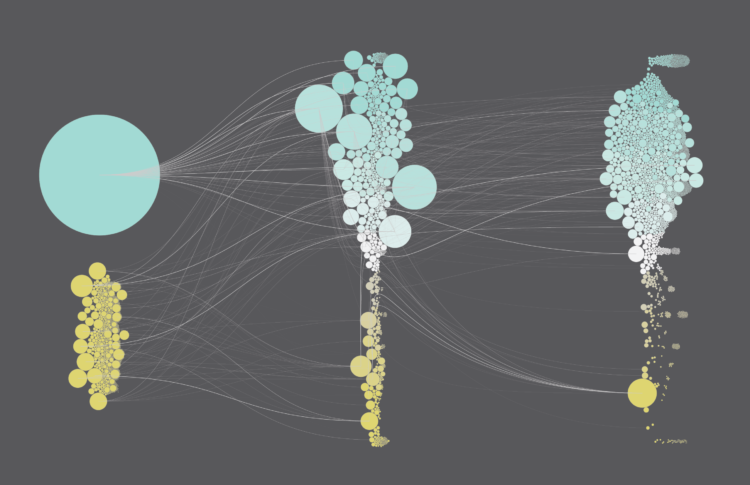

As expected, not a lot has changed between 2018 and 2019. The first graph shows the comparison of the Cantril Ladder scores (the principal happiness measure) for those 153 countries that appear in both reports. Each point represents one country, with the color coding indicating the geographical area (as listed in the network below).

Only three countries (as labeled) show large differences, with Malaysia becoming less happy, and two small African countries improving. As also expected, the European countries (green) tending to be at the top, and the African countries (grey) dominating the bottom scores.

Finland is still ranked #1, with even happier people than in 2018's report. New in the top-10 of the happiest countries is Austria (last years #12), which took the place of Australia (now #11). At the other end, South Sudan went down from 3.3 to 2.9 — this is not really a good start for the youngest state in the world. New to the lowest-ranking ten are Botswana (−0.1, down two places) and Afghanistan (−0.4, down 9).

A network analysisThe four measures of subjective well-being do not necessarily agree with each other, since they measure different things. To get an over view of all four happiness variables simultaneously, we can use a phylogenetic network as a form of exploratory data analysis. [Technical details of our analysis: Qatar was deleted because it has too many missing values. The data used were the simple rankings of the counties for each of the four variables. The Manhattan distance was then calculated; the distances have been displayed as a neighbor-net splits graph.]

In the network (shown below), the spatial relationship of the points contains the summary information — points near each other in the network are similar to each other based on the data variables, and the further apart they are then the less similar they are. The points are color-coded based on major geographic regions; and the size of the points represents the Cantril Ladder score. We have added some annotations for the major network groups, indicating which geographical regions are included — these groups are the major happiness groupings.

The rank-based network 2019 looks quite different to the one based on the explaining parameters 2018. Let us have a short look at the clusters, as annotated in the graph.

Cluster 1: The happiest — this includes the welfare states of north-western and central Europe (score > 6.7), as well as Australia, Canada and New Zealand (~7.3), Taiwan (the 25th happiest country in the world, 6.4) and Singapore (#34 with 6.3). For both the positive and negative measures of happiness, the countries rank typically in the top 50, with Czechia ranking lowest regarding positive affects (#74), while the people in Singapore (#1) and Taiwan apparently suffer the fewest negative affects (#2).

Cluster 2: Quite happy — includes countries like France, with 6.6 making it the happiest one of the group, plus countries along the southern shore of the Baltic Sea, as well as Japan, Hong Kong, but also also quite different countries from western Asia such as Kyrgyzstan and Turkmenistan, and Vietnam, the least happy (5.1) of the group. Common to all of them is that they rank in the top third of the standard derivation of the Cantril ladder scores, i.e. their people are equally happy across each country. Towards the right of the group, bridging to Cluster 3, we have countries that rank in the bottom third of positive affects. Potential causes are the high levels of perceived corruption, or the lack of social support and generosity, as in the case of Turkmenistan (#147 in social support, #153 in generosity).

Cluster 3: Not so happy — an Old World group of the lower half (Cantril scores between 5.2, Algeria, and 3.4, Rwanda) that are either doing a bit better than other, equally (un)happy countries regarding positive affects (Myanmar, Madagascar, Rwanda) or negative affects (e.g. Georgia, Ukraine), and are in the top-half when it comes to the SD.

Cluster 4: Generally unhappy — this collects most of the countries of the Sub-saharan cluster 2018 with Cantril scores ≤ 5, including three of the (still) unhappiest countries in the world: war-ridden Syria, the Central African Republic, and South Sudan, which rank in the bottom-half of all happiness rankings. When is comes to explanations, the ranking table is of little use: Chad, for example, ranks 2nd regarding perceived corruption, and the Central African Republic, generally regarded a as a

failed state, ranks 16th, and 14th regarding freedom — ie. it seems to have similar values here like the happiest bunch (Cluster 1).

Cluster 5: Pretty unhappy — this includes Asian and African countries that are not much happier than those of Cluster 4 but which rank high when only looking at positive affects. The reasons may include low levels of perceived corruption but also generosity, at least in the case of Bhutan (#25, #13) and South Africa (#24/#1), the latter being the most generous country in the world (something Guido agrees with based on personal experience).

Cluster 6: Partially unhappy — is a very heterogeneous cluster, when we look at the Cantril scores ranging from 7.2 for Costa Rica (#12), a score close to the Top-10 of Cluster 1, to 4.7 for Somalia (#112). Effectively, it collects all states that don't fit ranking-pattern-wise in any of the other clusters. For example, the U.S. (6.9, #19) and U.A.E. (6.8, #21) plot close to each other in the network because both rank between 35 and 70 on the other three variables, ie. lower than the countries of Cluster 1 with not much higher Cantril scores. Mexico, by the way (6.6, #23), performs similarly to the U.S. but ranks much higher regarding positive affects. The latter seems to be a general trend within the other states of the New World in this cluster.

Cluster 7: Really not happy — also covers a wide range, from a Cantril score of 6.0 (Kuwait, #51 in the world) to 3.2 (Afghanistan, #154). It includes the remainder of the Sub-saharan countries, most of the countries in the Arab world, and the unhappy countries within and outside the EU (Portugal, Greece, Serbia, Bosnia & Herzegovina). These are countries that usually rank in the lower half or bottom third regarding all four included variables.

Cluster 8: Increasingly unhappy — these countries bridge between Clusters 1 and 7, starting (upper left in the graph) with Russia (#68, top 10 regarding negative affects) and ending with Democratic Republic of Congo (#127, Congo Kinshasa in WHR dataset, ranking like a Cluster 7 country). In between are pretty happy countries such as Israel (#13) and unhappy EU members (Bulgaria, #97). The reason Israel is not in Cluster 1 is its very low ranking regarding both positive affects (#104) and not too high placement when it comes to negative affects (#69), but in contrast to the U.S. it ranks high when it comes to the SD of the Cantril scores — that is, the USA has a great diversity regarding happiness, from billionaires to the very poor, whereas the peoples of most countries are more equally happy. Other very-high ranking countries regarding the latter are Bulgaria, the least-happy country of the EU, and Mongolia.