By Donna Campisano, specialist, Communications, APHL

A vaccine to prevent measles has been available since 1963. And yet this highly contagious disease, characterized by fever, respiratory symptoms and a telltale body rash, is still with us.

While measles is thought of as a childhood illness, its outcomes can be far from benign.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 1 in 5 unvaccinated people who contract the virus will be hospitalized. One in every 20 children with the disease will develop pneumonia. And up to 3 of every 1,000 children infected will die from the neurological and respiratory complications measles cause.

Disease Outbreaks and the Role of Vaccine Preventable Disease Reference Centers

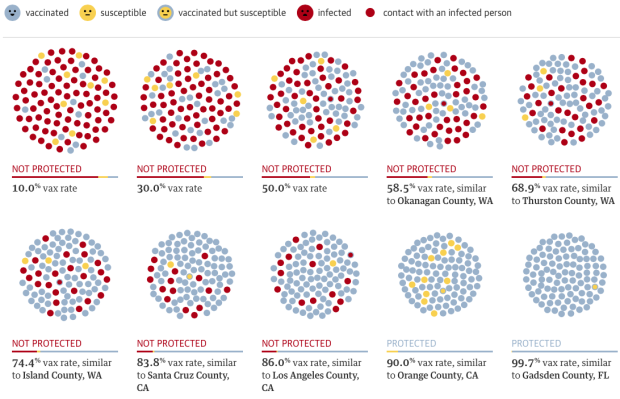

Thanks to a robust vaccination program, measles practically disappeared from this country and was declared eliminated in the US by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2000. But increased vaccine hesitancy and a return to global travel (most cases of measles in this country are imported from elsewhere) following the pandemic have officials concerned.

As of the first week in March, 45 measles cases from 17 jurisdictions have been reported to the CDC in 2024. Compare that to 58 total cases from 20 jurisdictions reported in all of 2023. Florida accounts for 10 of those cases, nine in one county alone. While the vast majority are children and teens, one is an adult. All 10 cases were reported in February, demonstrating how quickly cases can spread. And more cases are popping up every day. The CDC recently sent a team to Chicago to help with a measles outbreak clustered mostly in a migrant shelter. Eight cases have been confirmed in about as many days.

While the number of cases reported thus far in this country isn’t staggering, the same can’t be said for other parts of the world where vaccination rates are particularly dismal. According to WHO, measles cases increased 18% globally from 2021 to 2022 and deaths jumped by 43%.

In 2013, APHL, in partnership with CDC, established four Vaccine Preventable Diseases (VPD) Reference Centers to help reduce the diagnostic load of state laboratories and assist with the pathogen typing that’s necessary to detect the origin and spread of disease outbreaks.

These four centers—located in California, New York, Wisconsin and Minnesota—perform molecular testing for the viruses that cause measles, mumps, rubella (German measles), chickenpox, enterovirus (which can cause diseases like polio and hepatitis A) and MERS-CoV (Middle East respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus). The Wisconsin and Minnesota centers also perform bacterial pathogen testing.

Testing, both diagnostic and characterization, is performed using standardized methods developed by CDC and is available to public health departments free of charge. Submitting sites are assigned to one or two VPD Reference Centers depending on what services they need. Test results are reported to the submitting site and to CDC.

Detecting Outbreaks in Real Time

How do VPD Reference Centers help curb outbreaks?

To reduce vaccine-preventable diseases like measles and the burden they cause, officials—from clinicians to public health professionals to lab scientists—need details about what diseases are circulating where. And the more immediate the information, the more immediate a response.

To that end, APHL will be launching a VPD dashboard in the next few months. The VPD Reference Centers will submit monthly or bimonthly data reports to APHL detailing the number of specimens submitted to them for testing, how many tests were performed per pathogen and the number of positive specimens detected. That information will be fed into the publicly available dashboard.

The dashboard, along with the rapid detection of disease provided by member labs and the outreach conducted by public health officials, will play a pivotal role in responding to disease outbreaks. APHL and CDC will continue to work together to provide training and improve knowledge in identifying and curtailing disease outbreaks, whatever form they take, wherever they erupt.

The post Measles Outbreaks Still Occur: How the APHL/CDC VPD Reference Centers Are Working to Identify Them appeared first on APHL Blog.