A lot of ink has been spilled (bits transferred? attention drained? bandwidth clogged? liquids imbibed? anachronistic metaphors tortured?) with various arguments about the hierarchical nature of science and the race to better position oneself versus one’s colleagues. Whether it’s questions of appropriate authorship, proper acknowledgement, or implicit vs explicit signals for the valuation of individual contributions, it seems like there’s a new discussion every week. Many of these arguments seem to break down around the point where it’s realized that field A, sub-field 1 and field B, sub-field 6 have strikingly different cultures surrounding these issues and the present lessons/problems/solutions from A1 may run counter to the lessons/problems/solutions in B6 even though both use the same short-hand: postdoc problems, authorship problems, tenure credit.

These ongoing cultural dialogues spill over and often get mixed into the proposal and merit review process leading to a proliferation of different beliefs, local customs, and inherited “understandings” of how the system ought to work in your favor if only you had the “right sort” of partner, reviewer, history, etc. In DEB, this is manifest in questions about professional titles, proposal cover pages, biographical sketches and project responsibility.

In this post, we address some of the most frequently encountered myths in this area, with explanations of DEB processes and the supporting NSF policies.

Myth 1: A PI ranks above a Co-PI on an NSF proposal/grant.

Fact: Any persons designated by the institution as principal investigators are equally responsible for the direction of the project and submission of reports. We make no distinction in scientific stature between the designations of PI or Co-PI on a proposal/grant. This is explicit NSF-wide policy.

Any time you put multiple people on the cover page, they are officially all co-equal as PIs and you are telling us that “all of the individuals are equally responsible for the conceptual development of this project and will have equal responsibility for ensuring completion of the totality of the award requirements. If any one (or more) of the named individuals were to experience an incapacitating event this day, the remaining person(s) would be able to carry this project to completion in their absence.”

The only practical difference between Co-PIs is that the name on top is the “contact PI”. That’s not a mark of seniority, it’s a matter of organizational efficiency — if we sent all requests and notifications to all co-listed PIs we’d wind up with a lot on non-responses, duplicate responses, and contradictory responses and no way to determine which one had the final say. It is, however, the responsibility of the contact PI to communicate effectively between NSF and any Co-PIs.

Myth 2: NSF says I can’t be a PI or Co-PI because I’m not tenure-track.

Fact: NSF does not prohibit any individual[i] from being named as a PI or Co-PI based on employment status.

From the Grant Proposal Guide, “NSF welcomes proposals on behalf of all qualified scientists, engineers and educators.” “Qualified” depends on the nature of the project. “[O]n behalf of” is because proposals are not submitted by PIs, they are submitted by institutions[ii].

Because institutions officially submit proposals, they alone are responsible for determining who they are willing to endorse as (co-)responsible for the scientific direction of the proposal. So, the question of whether you, with your present title and employment arrangement, are eligible to be a PI on a proposal can only be addressed by you and your sponsored research office and the answer will vary. However, whether you can be a PI on an award is subject to final approval from NSF (that’s why you need to request approval to substitute PIs on an active award) and there are rare cases where an award might be delayed because of questions about the qualifications of the proposal PI.

NSF does make one specific pronouncement about PI status: we do not encourage naming graduate students as principal investigators on research grants. But this isn’t a ban (it’s just exceedingly rare) and there are other types of grants such as fellowships and dissertation improvement grants where graduate students are intended to be the person responsible for a proposal/grant.

Myth 3: I can only be a PI (on the cover page) of a proposal from my institution.

Fact: Following from the prior myth there are also often questions about requirements on institutional affiliation. But what is “my institution” anyway? Large numbers of researchers have multiple appointments with various academic, educational, non-profit, business, and foreign organizations: any one of which may be an eligible submitting institution.

Simply, you can be a PI of a proposal from any eligible institution that is willing to put you there.

We see proposals all the time with multiple PIs who would primarily associate with different institutions but were designated by the submitting institution as their co-responsible individuals. The contact PI is usually primarily/directly associated with (and usually draws salary from) the submitting institution, but NSF doesn’t require PIs to be employees of the institution and quite often the other names on the list may only be affiliated through sub-awards, intellectual collaborations or adjunct or courtesy appointments. For proposals with sub-awards, the GPG makes it clear that it is a-ok, but in no way required, for the researchers from the other organizations to be Co-PIs if all the institutions agree to it.

Myth 4: All PhD-level participants should be listed as senior personnel. Only PhDs can be senior personnel.

Fact: The Grant Proposal Guide explicitly defines 7 distinct categories of project personnel. There are two types of “senior personnel” and five types of “other personnel” tied to lines in the budget. Elsewhere, the GPG uses the slightly more nebulous term “other senior personnel” as a concise way of saying “faculty-equivalent researchers who aren’t (Co-)PI(s) but are making an important intellectual contribution through their work on this project under whatever professional title they may hold”.

All of the people named as project personnel, whether “senior”, “other senior” or just “other”, should have some sort of direct involvement in carrying out the project. But that’s not all! An entirely different category of individual/institutional involvement called “unfunded collaborations” exists to describe those involved with the project in ways other than carrying out the work (e.g., sending you stored samples, providing site access, etc.).

Of all of these ways for your name to possibly appear in a proposal, only one budget-defined sub-category, “Postdoctoral (Scholar, Fellow, or Other Postdoctoral Position)” specifically requires a PhD or equivalent. And, these Postdoctoral participants are considered “other personnel,” no “senior” involved.

All other personnel types, whether “senior” or “other” or “unfunded collaborator” are defined by the role in the project. The definitions are silent about any prior graduate degree(s).

For instance, Principal Investigators are not required to be PhDs; there are entire classes of awards (e.g., DDIGs) that are specific to pre-PhD individuals (see Myth #2 above) and in other fields and different institution types, it’s common to have professional researchers at the Masters level. There are many senior personnel without PhDs.

There are also many cases, where it’s inappropriate for PhD-level contributors to be listed as any sort of senior personnel. The head of some facility who has agreed to give you access but isn’t doing the work would be an unfunded collaborator: there’s no justification for identifying this person as senior personnel and reviewers will readily note that they aren’t actually working on the project. Other individuals primarily providing a specialty service to the intellectual team (someone being paid to carry out a specific technical task such as a professional evaluator of an educational program or a gene sequencing firm, etc.) may be most appropriately identified as “Other Professionals” (budget Line B) or Consultants (budget Line G3).

Myth 5: I’m on a postdoctoral appointment so I must/can’t… [too many variations to list]

Fact: Postdocing can be rough (citation: see any day on twitter). And, figuring out how to obtain funding for your science while postdocing can be a big part of that[iii]. We get a lot of inquiries about this and it generates lots of problems.

Questions of the usual “can I be a PI” sort are addressed in Myths 2 and 3 above. (Recap: It’s up to your institution.)

Most problems arising from postdocs on proposals can be avoided by following just one rule of thumb: BE CONSISTENT IN THE PROPOSAL.

More specifically, within a proposal an individual who is employed by an institution on a postdoctoral appointment can be a PI OR a postdoc but never both at the same time. You can’t mix and match documentation in your proposal between the two roles.

Consider this: if there’s a postdoc in the proposal, there needs to be a mentoring plan as part of the proposal that describes how the PI will impart new knowledge and skills to the postdoc. If a single individual is both PI and postdoc, that arrangement falls apart.

The title of your position doesn’t matter to us, but how you are represented in the proposal does. So someone on a postdoctoral appointment preparing a proposal as a (Co-)PI should complete all the parts of a proposal including the budget as a (Co-)PI and ignore anything that says “for post-docs…” because you aren’t a postdoc in the context of the proposal; you’re a (Co-)PI. On the other hand, if you want to be listed as a postdoc on the proposal (we think this is a good idea, see the next myth), then your PI must include a mentoring plan, must list any salary for you on the postdoc line of the budget, and must not put you on the cover page as a Co-PI.

Myth 6: Appointing that “junior” researcher to a PI or Co-PI role earns them credit.

Reality-check[iv]: That’s a highly suspect, possibly cynically exploitative, and potentially damaging move for the junior recipient of the “largesse”. Postdocs and grad students, please heed this warning.

Stop and consider who does this benefit? How (or for what purpose)? What is given up? Because, from our perspective this doesn’t favor the junior researcher. Our reasoning is as follows:

Will this help to get the project funded? Some reviewers may buy this maneuver and give the senior researcher collegiality points for promoting a junior person. However, it’s just as likely to be seen as a risk, “why is the less capable person being put in charge?” or a superficial move, “we all know the senior researcher is really in charge.” And, ultimately, the reviewers provide advice. NSF makes the decisions. We’ve seen this before and its effect on the post-review decision-making is generally nil.

Will this help to land a tenure-track position? Possibly, but publications produced as a postdoc or research associate, independent fellowships, and a strong recommendation letter from a successful PI would also demonstrate your abilities much more substantially while preserving beginning investigator status.

What happens if it gets funded? Elevating a postdoc or other (non-tenure track) junior researcher to a PI position does earn them credit as a “PI” in the NSF system. Will this help with tenure? Probably not; grants you received prior to your tenure track position don’t generally count in a tenure package and even if it did count it’s easily discounted by the presence of the senior researcher. What else does PI status mean? Well, for one, it means they will show up as a funded PI and, as we’ve shown, future funding decisions are strongly biased toward giving the money to unfunded PIs. It also means they are no longer eligible as a “beginning investigator” — that person loses the ability to submit their BIO proposals to other funders for simultaneous consideration[v] so it’s limiting their future submission opportunities.

The ONE AND ONLY CASE where this sort of change is probably a good thing is when a postdoc or other PhD-wielding-non-tenure-track-researcher lands that first TT position between a preliminary and full proposal and so could become a PI on a grant that will count fully toward their tenure package.

Myth 7: Being the “lead” PI on a collaborative proposal is more valuable than being the PI of a non-lead collaborating proposal.

Fact: The lead PI in a multi-institutional collaborative project is responsible for more paperwork at the proposal submission stage but if the project is funded, each institution gets a separate award and each PI gets their own credit for a project. This is because once the awards of a collaborative project are made, there’s no longer a link between the records. Each PI shows up as a PI on a separate award with the same independent reporting requirements, independent management responsibilities, and nothing in the public record to identify who “led” at the proposal stage.

We, DEB, can go back to the proposal records and force things together to generate reports that reflect those relationships when necessary, but as far as the official award records are concerned, each PI is responsible only for their award and has no relationship to any other. Some efficiency might be gained from coordinating aspects of reporting for instance, but that’s not a requirement or specific authority granted to one PI above all others.

In fact, the “lead” PI on a multi-institutional collaborative has less responsibility than the contact PI on a collaborative managed as a single proposal with sub-awards, because in that case the contact PI/awardee institution is responsible for overseeing the use of funds and reporting accomplishments of institutions external to their own finance and administrative systems. A major incentive for multi-institutional instead of sub-award collaboration is that separate awards are less work for the lead institution if an award is made.

Myth 8: I need to be a PI or Co-PI to include my biographical sketch.

Fact: The Grant Proposal Guide is very clear on the “who” of biosketches: they should be present for all senior personnel [(Co-)PIs, Faculty Associates, and that nebulous “other senior personnel”], but it also says they can be provided for postdocs, other professionals, and student RAs if they have particularly relevant qualifications[vi].

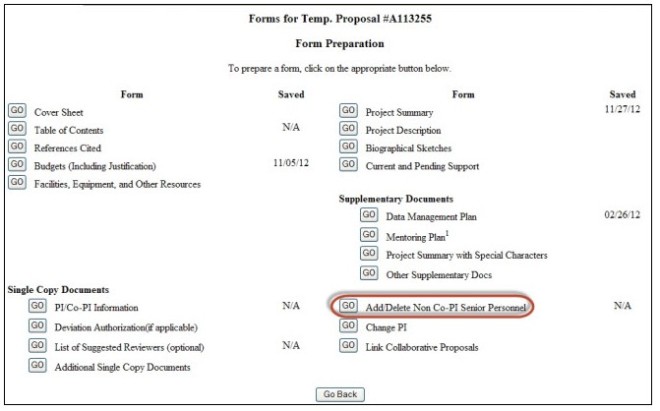

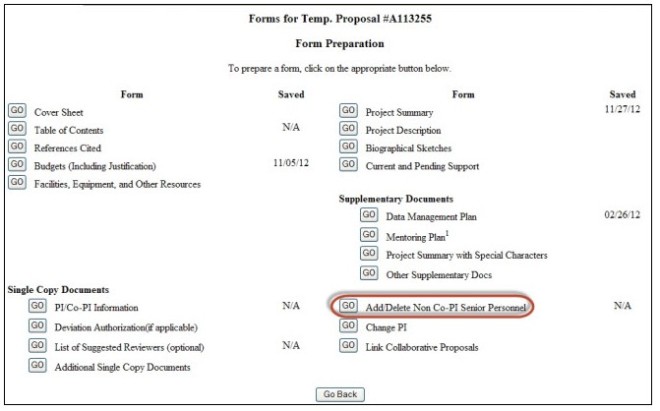

Many of you are already aware that FastLane creates a spot for a biographical sketch for each of the up to 5 (Co-)PIs on a proposal, which is the likely source of the myth, but figuring out how to do this for anyone else who should/could have one has been a perennial problem.

So, how do you add biosketches of collaborators not listed on the cover page?

On the proposal prep screen in FastLane you can select the button shown below to enter in the names of any additional people and create spaces in which to upload biosketches.

PLEASE make a note of this advice because as FastLane heads towards more and more pre-submission compliance checking, time-worn workarounds, like uploading all the biosketches as a single PDF, are going to stop working and eventually block your ability to complete submission.

The label says “senior personnel” but that’s misleading because it doesn’t actually set anything with respect to the persons’ roles or responsibilities so you can use this to add biosketches for other senior personnel as well as any other qualifying individuals. It would be awesome if they’d fix that label, but at least it works.

So, with this one simple step, any additional names of individuals beyond the cover page PIs can be associated with the proposal for the purpose of adding biosketches.

[i] Except for the group “persons barred from receiving federal funds“.

[ii] Though an individual can register themself as an institution.

[iii] If you’re in this situation, may we interest you in our previous post on the AAAS Policy Fellowships?

[iv] Since this response is more about experience than referenced current policy, we’ll drop the “fact” label.

[v] Proposals in NSF/BIO are not allowed to be concurrently under consideration with other federal funders; this policy is waived for “beginning investigators” who have never held a federally-funded research grant from any agency.

[vi] Please note however, that this guidance applies to FULL PROPOSALS we have specific restrictions on who can be submitting biosketches with preliminary proposals in DEB.

Academic conferences are the annual meeting places for scientific communities to network, present their latest research, and celebrate the year’s achievements. Conferences like these are a bit different from, say, a science fiction convention or

Academic conferences are the annual meeting places for scientific communities to network, present their latest research, and celebrate the year’s achievements. Conferences like these are a bit different from, say, a science fiction convention or