Shell hunters in sunglasses examine a lion’s paw, a prized find on Sanibel Island in Florida, 1959. Photograph by Paul Zahl, National Geographic Creative

Adam's Blogroll: click through to the author's blog

Shell hunters in sunglasses examine a lion’s paw, a prized find on Sanibel Island in Florida, 1959. Photograph by Paul Zahl, National Geographic Creative

Shell hunters in sunglasses examine a lion’s paw, a prized find on Sanibel Island in Florida, 1959. Photograph by Paul Zahl, National Geographic Creative

Going to conferences is one of my favorite aspects about being a scientist. As a PhD student, I spend a lot of my life in solitude: when I read new literature, when I program new experiments, or when I conduct … Continue reading

The post Highlights from the 2015 Meeting of the Vision Sciences Society appeared first on PLOS Blogs Network.

Posted by in #TheDress, conference review, conferences, Florida, illusions, student life, The Student Blog, Vision Science Society

By Melissa Murray Jordan, senior environmental epidemiologist, Bureau of Epidemiology, Division of Disease Control and Health Protection, Florida Department of Health

Private wells in many central Florida counties have been found to contain levels of arsenic above the federal maximum containment level (MCL) of 10 μg/L (micrograms per liter). Knowing it is present is important to the public’s health; but how serious is this? Even exposure to low amounts of arsenic can potentially lead to an abnormal heart rhythm, damage to blood vessels, and a tingling sensation in hands and feet. Inorganic arsenic, the type in this water, is a carcinogen when consumed over many years. High levels of exposure to arsenic may lead to death. To address this known contamination, the Florida Safe Water Restoration Program provided filters or bottled water to households with arsenic levels in private wells between 10 μg/L and 50 μg/L. In partnership with the Florida Department of Environmental Protection, the Florida Department of Health (FDOH) decided to test the effectiveness of this program as well as explore any further impact of the contaminated water on residents living in areas of concern.

The study targeted Hernando County where nearly 400 of the 1,200 wells tested had elevated arsenic levels. This time, scientists wanted to understand if residents who weren’t drinking unfiltered well water (people who were drinking bottled water or using a filter in their homes) were still ingesting unsafe levels of arsenic through other unfiltered tap water in the home. It is widely known that arsenic exposure often occurs from drinking water, but what about exposure to water in other ways? What about brushing your teeth with unfiltered water? Or when cooking with unfiltered water?

A critical initial step of this project was forming a workgroup with representatives from many disciplines to inform various steps of the study:

Funding from CDC’s Environmental Public Health Tracking program allowed the state to engage these experts and ensured a high-quality study.

From April through July of 2013, 360 individuals from 166 households participated in the study. Nearly 50% of the participants were from control households: households with well water arsenic levels below 8 μg/L (below MCL). The other half were classified as case households: households with arsenic levels exceeding 10 μg/L (at or above the MCL). Participants provided urine and water samples, and completed a questionnaire on water consumption, dietary history and other possible sources of arsenic exposures. Water and urine samples were sent to the public health laboratory in Jacksonville, Florida for analysis of total arsenic.

The majority of case households (59.8%) reported bottled water as their most common source of drinking water, and 47.5% reported using bottled water for cooking. However, the majority of case households reported using unfiltered well water to brush their teeth (88.7%).

In many biomonitoring studies, only adults participate. This study also included children. Simply because of their size, a small amount of a chemical can have a larger impact in a child than the same amount in an adult. Scientists felt it was valuable to look at a range of people without omitting the smallest members of the community. Additionally, children tend to have different behaviors from the adults in their homes. For example, they may take baths rather than showers – and kids may be more likely to ingest that bath water. Fortunately, no children in this study were found to have elevated levels of inorganic arsenic.

Results: Residents using filtered or bottled water for drinking were not at an increased risk for arsenic exposure through other unfiltered household water sources.

The distribution of filters and bottled water was helping to prevent residents from exposure to arsenic. While testing for contaminants in the wells was an important first step to understanding the problem, biomonitoring provided a more complete picture of the full impact on a population. This was obviously good news to the residents and researchers alike.

The National Geographic Found Tumblr is now Webby award-winning! We recieved the People’s Voice award for Best Use of Photography.

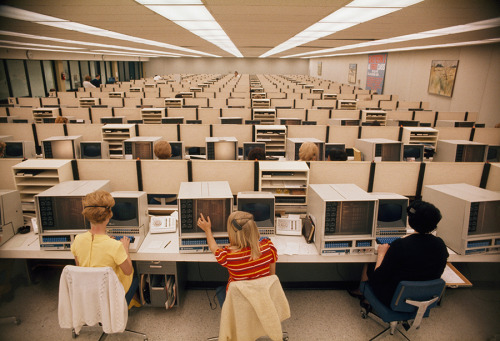

Operators man computers at Eastern Airlines’ reservations center in Miami, November 1970.Photograph by Bruce Dale, National Geographic Creative

By Tyler Sharp

By Tyler Sharp

2013 was a banner year for dengue in the United States: an outbreak with 22 associated cases was identified in Florida; another outbreak was detected in south Texas along the U.S./Mexico border; Aedes aegypti, the most efficient mosquito vector of dengue, was detected in central-California; a locally acquired dengue case was detected outside of NYC; and Puerto Rico experienced a sizeable dengue epidemic that had been ongoing since late 2012. So, what’s next? Is this par for the course, or was 2013 an anomaly? In this blog, I’ll discuss the history of dengue in the U.S., what the future might hold, and what you can do to reduce your risk of getting infected while at home or abroad.

History of Dengue in the U.S.

Dengue is a tropical illness that causes fever, body pain, severe headache and eye pain, and sometimes minor bleeding from the nose or gums. Four different but related viruses can cause dengue, all of which are transmitted by mosquitoes of the Aedes genus. Because immunity against one virus does not protect you from infection with the other three, you can get dengue up to four times in your life. Around 5% of dengue cases progress to severe dengue, which can result in severe bleeding, shock, and even death. Although most Americans have never heard of dengue because there is not much of it in the continental United States, dengue is actually quite common throughout the tropics, where 400 million infections occurred in 2010.

Dengue is a tropical illness that causes fever, body pain, severe headache and eye pain, and sometimes minor bleeding from the nose or gums. Four different but related viruses can cause dengue, all of which are transmitted by mosquitoes of the Aedes genus. Because immunity against one virus does not protect you from infection with the other three, you can get dengue up to four times in your life. Around 5% of dengue cases progress to severe dengue, which can result in severe bleeding, shock, and even death. Although most Americans have never heard of dengue because there is not much of it in the continental United States, dengue is actually quite common throughout the tropics, where 400 million infections occurred in 2010.

Despite relatively low case counts in recent decades, dengue is no stranger to the United States. Dr. Benjamin Rush, a signatory of the Declaration of Independence, documented a dengue outbreak in Philadelphia in 1780. Ships arriving from foreign ports were bringing mosquitoes and infected people back to port cities in the U.S., where local outbreaks then followed. This continued along the eastern seaboard and Gulf coast for the next 150+ years: an outbreak in 1873 affected an estimated 40,000 residents of New Orleans, and another in 1922 made its way through the entire Gulf coast. The last recorded dengue outbreak in the continental U.S. occurred in 1945 when a soldier returning from Guyana to Louisiana brought the virus home with him, resulting in an outbreak in which 145 people were affected.

Aedes Eradication Campaign

So why were no dengue outbreaks identified in the U.S. between 1945 and now? Most prominently, the chemical DDT was used beginning in the 1940s to nearly eliminate Aedes mosquitoes, which also transmit yellow fever and chikungunya, from the Americas. However, before the mission was completed, the detrimental effect of DDT on the environment was made public and elimination efforts were halted. Consequently, over the next several decades mosquito populations gradually re-established themselves in the U.S. and abroad. As the burden of dengue in the tropics began to increase in the 1980s and 1990s and Americans began to travel internationally more frequently, more and more travelers began to return to the U.S. with the unwanted souvenir of dengue.

So why were no dengue outbreaks identified in the U.S. between 1945 and now? Most prominently, the chemical DDT was used beginning in the 1940s to nearly eliminate Aedes mosquitoes, which also transmit yellow fever and chikungunya, from the Americas. However, before the mission was completed, the detrimental effect of DDT on the environment was made public and elimination efforts were halted. Consequently, over the next several decades mosquito populations gradually re-established themselves in the U.S. and abroad. As the burden of dengue in the tropics began to increase in the 1980s and 1990s and Americans began to travel internationally more frequently, more and more travelers began to return to the U.S. with the unwanted souvenir of dengue.

Present-day dengue in the U.S.

Following a large dengue epidemic in Mexico that spilled over into south Texas in 2005, an investigation revealed not only that stable populations of Aedes mosquitoes were established along the Texas side of the U.S.-Mexico border, but also that 39% of residents had been previously infected with a dengue virus. Because several of these individuals had never left the United States, this demonstrated that dengue virus had been circulating in south Texas.

On the other side of the Gulf of Mexico, in 2009 a dengue outbreak was detected in Key West, Florida, which was likely caused by importation of the virus in a traveler returning from Central America. The outbreak ultimately resulted in 5% of the small island community being infected. Dengue cases resulting from infection in Florida continued to be detected in the area in 2010 and 2011, and one report suggested that the virus may have become established in the region. Thankfully, no additional locally-acquired cases were reported in Key West in 2012, although dengue did pop up in Florida again in 2013. These outbreaks have made it clear that although rare, conditions do exist for localized outbreaks in parts of the U.S.

This week CDC Dengue Branch and co-investigators in Texas and New Mexico reported a locally acquired, dengue-related death in the continental United States. Although the patient died from a rare complication of dengue called hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis, this is the third dengue-related death ever in the United States. Although our investigation couldn’t confirm where the case-patient was infected, she hadn’t traveled out of the country recently, so she must have been infected either in New Mexico, where she was vacationing before she got sick, or in her home state of Texas. This case was a startling demonstration that there may be more dengue in the U.S. than we realize, and that physicians should be on the look-out for cases.

What’s next

The burden of dengue in the Americas has increased roughly 30-fold since 1950, and one study showed that dengue-related hospitalizations in the United States tripled between 2000 and 2007. So, dengue cases will likely continue to show up in greater numbers in the U.S. until we have a safe and effective dengue vaccine or other intervention to prevent dengue. Moreover, two mosquitoes capable of transmitting dengue, Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus, are present mostly in the southern United States, but have recently been found as far north as Chicago and New York. Therefore the possibility of local outbreaks in the U.S. after infected travelers return home is real. Nonetheless, factors such as population density, frequent use of air conditioning, and other lifestyle differences that limit our exposure to Aedes mosquitoes reduce the likelihood of sustained dengue outbreaks in the continental U.S. Therefore, Americans are more likely to get dengue while traveling in Latin America, for example to large international events like the World Cup, than they are to get dengue at home. Nonetheless, new introductions of the virus will continue, some of which will result in local dengue outbreaks.

The burden of dengue in the Americas has increased roughly 30-fold since 1950, and one study showed that dengue-related hospitalizations in the United States tripled between 2000 and 2007. So, dengue cases will likely continue to show up in greater numbers in the U.S. until we have a safe and effective dengue vaccine or other intervention to prevent dengue. Moreover, two mosquitoes capable of transmitting dengue, Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus, are present mostly in the southern United States, but have recently been found as far north as Chicago and New York. Therefore the possibility of local outbreaks in the U.S. after infected travelers return home is real. Nonetheless, factors such as population density, frequent use of air conditioning, and other lifestyle differences that limit our exposure to Aedes mosquitoes reduce the likelihood of sustained dengue outbreaks in the continental U.S. Therefore, Americans are more likely to get dengue while traveling in Latin America, for example to large international events like the World Cup, than they are to get dengue at home. Nonetheless, new introductions of the virus will continue, some of which will result in local dengue outbreaks.

What to do about it

To protect yourself against getting dengue, be aware of the risk of dengue while at home or traveling to the tropics, as well as the prevention approaches you can take to avoid mosquito bites (regular use of mosquito repellent, staying in buildings with air conditioning and/or window screens, seeking medical care if experiencing a fever during or soon after travel). Residents of states where Aedes mosquitoes are present can reduce their risk of spreading the virus by disposing of, emptying or covering water containers that serve as mosquito breeding sites (e.g., trash, discarded tires, kiddie pools). These strategies reduce the chances that a returning traveler could get bitten in the U.S. and create a local outbreak. Lastly, having a pre-travel health care consultation with your health care provider or a travel medicine specialist can provide additional information about dengue and other travel-associated risks that weren’t covered here.

Although the world is preparing for the introduction of a dengue vaccine, it is likely to be at least a few years before one is commercially available. Until that time, dengue will become more and more familiar to Americans, both at home and abroad.

Posted by in CDC, dengue, Disease Investigation, Disease Outbreak, fever, Florida, key west, mosquito, Prevention/Vaccination, Response, Texas, Vectorborne

In a fish-eye’s view, tourists peer down at aquarium fish in Miami, Florida, 1963.Photograph by Winfield Parks, National Geographic

Women enjoy the benefits of a heated whirlpool in Saint Petersburg, Florida, 1973.Photograph by Jonathan Blair, National Geographic

A swimmer from a houseboat joins women diving in Weeki Wachee’s pristine spring waters in Florida, 1955.Photograph by Bates Littlehales, National Geographic

Posted by in 1950's, Florida, history, Littlehales, natgeo, photograph, Vintage

A diver holding a hose for breathing compressed air feeds fish at Weeki Wachee Springs, Florida, January 1955.Photograph by Bates Littlehales, National Geographic

Posted by in 1950's, Florida, Littlehales, Mermaid, natgeo, underwater, Vintage