Justin Power

[This is a guest-post by Justin Power, and the 3rd part of our miniseries on sign language manual alphabets]

In Guido’s most recent post in this miniseries on manual alphabet evolution in sign languages, he discussed the role of character mapping on networks in phylogenetic inference. He pointed out how we used this approach to infer evolutionary pathways of languages, and why this step in exploratory data analysis is important, given the complexity of the underlying signal in this data set.

In this new post, I take up the topic of hand-shape evolution in more detail, explaining some of the complexities involved in studying sign language evolution. I will specifically look at how we can identify both vertical and horizontal processes in the evolution of hand-shapes.

Introduction

We know very little about how signs and hand-shapes actually evolve. There have been a few studies — most of them from decades ago — comparing American Sign Language in videos and dictionaries from the early 20th century with then contemporary forms (Frishberg 1975; Battison et al. 1975). One study in particular argued that, as a sign language emerges in a community of signers, crystallizing into a stable linguistic system, the signs evolve in a quasi-teleological way from earlier, more gesture- or pantomime-like forms to more language-like forms, cutting similar evolutionary pathways leading to more constraints on articulation and to general systematization.

But what happens (in this story) once sign languages become linguistic systems? Do they continue evolving, as happens in spoken languages? If yes, how? Investigating these kinds of questions was one of my motivations for tracking down historical examples of manual alphabets for over a dozen sign languages. The pay-off (besides the thrill of the treasure hunt) is that, by tracing hand-shapes through historical examples and comparing them with contemporary sign languages, we can infer the vertical and horizontal evolutionary processes affecting sign languages and hand-shape forms.

Vertical and horizontal aspects of hand-shape evolution

Consider part of the Neighbor-net from our paper (see Part 1) including the Austrian-origin and Russian groups in the figure below. Russian 1835 is the earliest manual alphabet in our sample published in Russia (St. Petersburg); and Danish 1808, in the Danish subgroup, was published in Copenhagen.

While the two manual alphabets are found in different neighborhoods in the graph, they share a number of hand-shapes, some of which were (and still are) shared widely throughout Europe, for reasons that we discuss in the main paper.

One such hand-shape represents the Latin / Cyrillic letter "A" in both Danish 1808 and Russian 1835, as illustrated in the timeline here.

Note the position of the thumbs at the bottom of the figure: in both early examples, the thumb is adjacent to the bent index finger. In an example from Danish SL in 1907 (and subsequently in 1926 and 1967), the position of the thumb has shifted across the index finger. For Russian SL, too, the position of the thumb in the contemporary hand-shape representing the Cyrillic letter A has crept across the index finger to the front of the fist (the hand-shape in the figure is my attempt to reproduce the source; see here for the real thing).

There are two points to note here in connection with evolutionary processes. First, these changes in thumb position appear to have a vertical aspect: as signers in a community used these hand-shapes and transmitted them to later generations, they also modified the forms in subtle ways, perhaps unconsciously in a process with analogies to sound change in spoken language.

Second, the changes also include a horizontal aspect: the forms evolved in similar ways, as the two signing communities converged on the same shape (apparently) independently, possibly due to similar articulatory or perceptual pressures. The horizontal aspect of this process contributes to signal incompatibility in the dataset underlying the network — the more convergence there is, then the less tree-like will be the Neighbor-net (in this case, the more spiderweb-like).

Convergence

In addition to the preceding example, a typical case of convergence can be seen in the independent creation of similar hand-shapes to represent the Greek and Cyrillic letter "Г".

Beginning again with the main Neighbor-net in the figure immediately above, we see that Russian 1835 and contemporary Greek SL are found in different neighborhoods, with Greek in the French-origin group. The two languages, however, share the Г-representing hand-shape (the Russian form is from Fleri 1835, while the Greek form is, again, my own hand; see here for the real one). Because Greek SL is the only language in the French-origin group to share this hand-shape with the Russian group, there is a clear suggestion of a horizontal process that resulted in similar hand-shapes across unrelated languages. The most likely processes here are convergence due to the independent creation of iconic representations of the written letter; or lateral transfer — called borrowing in linguistics — via some historical instance of contact between signers of the two languages. [My intuition is for the former explanation.]

Borrowing

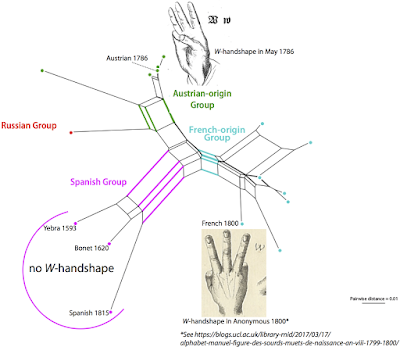

The final example deals with a clear case of borrowing. The figure below shows the time- / taxon-filtered Neighbor-net, including historical manual alphabets up to about 1840 (see Part 2), but only annotated with the relevant languages.

The two earliest manual alphabets in our dataset were published in Madrid in 1593 (de Yebra) and 1620 (Bonet). In neither case do we see any trace of a hand-shape representing the letter "W", which was not needed to represent these Latin alphabets. Later, too, manual alphabets published in Spain in 1815, 1845, and 1859 still did not include the letter "W". In contrast, in Austrian 1786 and French 1800 (as well as other languages), hand-shape forms representing the letter W are found in the earliest examples we have for those languages. Some 160–230 years later, however, we find similar forms for "W" in contemporary Austrian, French and Spanish SLs. We deduce that contemporary Spanish SL did not inherit the "W" hand-shape from the 19th century Spanish manual alphabets. Instead, the hand-shape may have been borrowed from some other language, possibly French SL given its influence on deaf education in Europe, or possibly later from the International Sign manual alphabet (also part of the French-origin Group).

Conclusion

As these examples show, there are different types of horizontal processes contributing to conflicting signal in the data set. Using the splits network graphs together with historical examples of manual alphabets, we can untangle the horizontal signal in many cases. The approach has also given us some insight into the evolutionary processes contributing to the diversity of contemporary sign languages, a topic that we plan to investigate more fully.

Cited literature, further reading and data

- Battison, Robin, Harry Markowicz, & James Woodward (1975) A good rule of thumb: Variable phonology in American Sign Language. In Ralph W. Fasold & Roger W. Shuy (eds.), Analyzing Variation in Language: Papers from the Second Colloquium on New Ways of Analyzing Variation, Part 3, pp. 291–302. Washington D.C.: Georgetown University Press.

- Bonet, Juan Pablo (1620). Reduction de las letras y arte para enseñar a ablar los mudos. Madrid: Francisco Abarca de Angulo.

- Fleri, Viktor I. (1835) Глухонемые, рассматриваемые в отношении к их состоянию и к способам образования, самым свойственнымих при. St. Petersburg:Типография А. Плюшара.

- Frishberg, Nancy 1975 Arbitrariness and iconicity: Historical change in American Sign Language. Language 51(3): 696–719.

- Yebra, Melchor de (1593) Libro llamado Refugium Infirmorum: Muy util y prouechoso para todo genero de gente : En el qual se contienen muchosauisos espirituales para socorro de los afligidos enfermos, y para ayudar à bien morir a los que estan en lo ultimo de su vida ; con un Alfabeto de S. Buenauentura para hablar por la mano. Madrid: Luys Sa[n]chez

Other posts in this miniseries

- Stacking networks based on sign language manual alphabets – introduction and principal networks used in our study

- Character cliques and networks: mapping haplotypes of manual alphabets – how we explored the principal signals in our matrix