(cross-posted from easternblot.net)

The day after the Brexit referendum I went to visit a museum dedicated to two German immigrants, and some of England’s most prolific astronomers.

Siblings William and Caroline Herschel lived in Bath during the 18th century, in New King Street. Two and a half centuries later, the street was quiet, with recycling bags outside every door, and a few straggling hopeful “Vote Remain” posters in some of the windows. The Herschels used to live at number 19, where the front door was now partly open.

Siblings William and Caroline Herschel lived in Bath during the 18th century, in New King Street. Two and a half centuries later, the street was quiet, with recycling bags outside every door, and a few straggling hopeful “Vote Remain” posters in some of the windows. The Herschels used to live at number 19, where the front door was now partly open.

I stepped inside, into a very normal corridor of a very normal terraced house. Normal, aside from a man standing behind a desk in the room at the far end of the corridor, welcoming me to the museum, and explaining that I could walk around the house, which was entirely converted to a museum devoted to the Herschels’ life and work.

I started at the basement level, which had access to the garden. This was the very garden in which William Herschel discovered the planet Uranus in 1781.

Until his discovery, there were only six known planets in the solar system: Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn. All of these could be seen with the naked eye, and had been recognized as planets from the way they travelled across the night sky and changed position in relation to the stars.

The remaining planets were too far away to see. There were telescopes at the time, but none were good enough to see that far into space with enough detail. William Herschel developed a telescope that made it possible to see further into space in more detail. He had a workshop attached to his home, where he worked on his telescopes, and he soon became the world’s foremost telescope maker.

The remaining planets were too far away to see. There were telescopes at the time, but none were good enough to see that far into space with enough detail. William Herschel developed a telescope that made it possible to see further into space in more detail. He had a workshop attached to his home, where he worked on his telescopes, and he soon became the world’s foremost telescope maker.

But despite discovering a whole new planet, astronomy was just Herschel’s hobby at the time. His day job was as organist for the Octagon Chapel in Bath. The organ is no more, but a set of pipes from the old organ are on display in the music room, upstairs in the museum.

The music room also has several objects related to the life Caroline Herschel. She initially came to England to help her brother around the house and to pursue a professional singing career. When William’s astronomy hobby slowed turned into a full career, she became more involved with that, and made a few astronomical discoveries of her own.

The music room also has several objects related to the life Caroline Herschel. She initially came to England to help her brother around the house and to pursue a professional singing career. When William’s astronomy hobby slowed turned into a full career, she became more involved with that, and made a few astronomical discoveries of her own.

When William discovered the planet Uranus, he proposed to name it Georgium Sidus (George’s Star) to honour England’s King George III, who was also Duke of Herschel’s hometown Hanover. The name didn’t stick, because other astronomers preferred a more international name, but in 1782, William Herschel was employed as King’s Astronomer. A few years later, the king also paid Caroline a salary for her assistance to William, making her the very first woman in the world to receive a salary for scientific work.

In the gift shop on the ground floor of the house I picked up two booklets about the Herschels’ musical careers, before heading back to the train station.

In the following days, it quickly became clear that in the wake of Brexit it has become quite difficult for European scientists in the UK, when nobody knows whether they will need visas, or whether new researchers will even want to come. Even British scientists are already having trouble applying for collaborative grants with their EU colleagues, as they might not qualify for the funding in a few years, and hinder the joint application.

So how did the Herschels get to work in England so easily, centuries before the EU? There may not have been a Europe-wide open borders scheme at the time, but there was an arrangement between Hanover and England, since they shared a ruler (King George III), so it was an obvious and easy choice to move between the two places.

I wanted to visit the museum because I was interested in the Herschels’ dual interests in music and science, but the date of my visit couldn’t have been more poignant, as the Herschel story is a textbook example of the work that foreign scientists have contributed to the UK.

Filed under: Have Science Will Travel Tagged: Bath, Brexit, Caroline Herschel, William Herschel

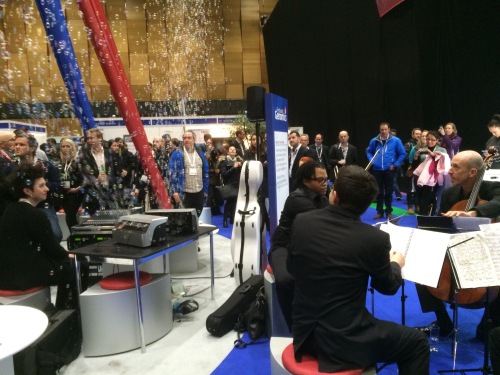

There is a time and a place for complex atonal music, and perhaps the drinks reception of a genomics conference at the Excel Centre was not it. Through the chatter it wasn’t always easy to hear what the string quartet was doing, and meeting attendees were confused about the performance. “I thought they were still tuning”, said one of the guests.

There is a time and a place for complex atonal music, and perhaps the drinks reception of a genomics conference at the Excel Centre was not it. Through the chatter it wasn’t always easy to hear what the string quartet was doing, and meeting attendees were confused about the performance. “I thought they were still tuning”, said one of the guests.

This was not the first performance of Music of the Spheres. It had previously been set up in a large empty building, a gallery along the coast, and Hornsey Town Hall. The string quartet can’t be everywhere, but the bubbles are always there, and form the core part of the work. In fact, Jarvis turned on the bubble machine a few times during breaks at the Festival of Genomics. Without the string quartet, this created an effect of simple party entertainment, not out of place at this conference, which also featured a lively talk show and a treadmill challenge. People engaged with the bubbles by photographing them, popping them, or shielding their coffee cups from soapy surprises. Many of them were unaware that each bubble contained fragments of DNA encoding a piece of music.

This was not the first performance of Music of the Spheres. It had previously been set up in a large empty building, a gallery along the coast, and Hornsey Town Hall. The string quartet can’t be everywhere, but the bubbles are always there, and form the core part of the work. In fact, Jarvis turned on the bubble machine a few times during breaks at the Festival of Genomics. Without the string quartet, this created an effect of simple party entertainment, not out of place at this conference, which also featured a lively talk show and a treadmill challenge. People engaged with the bubbles by photographing them, popping them, or shielding their coffee cups from soapy surprises. Many of them were unaware that each bubble contained fragments of DNA encoding a piece of music.

Of mice and men?1

Of mice and men?1